Cruising a Wormhole: When Minnegasco Met Red Owl

My entryway into Star WallowingBull’s (Ojibwe and Arapaho) worlds and works began in the late fall of 2023. Through these unspooling engagements, the breadth and depth of WallowingBull’s practice would crystalize as if strings zigzagging from beyond the horizon lines of land and cosmic bodies. These works that I would become guest and confidant to comprise WallowingBull’s sixth solo show with Bockley Gallery, Mapping and (Meta)Morphing. Spanning medium, scale, and temporal orientation, WallowingBull precisely warps and wraps time and space. He refuses the calcified borders that attempt to constrain place, memory, and the ever-spinning web of belonging. Across colored pencil on paper and acrylic on canvas, WallowingBull flattens the visual planes of his works. In this, he creates porous imagery: capacious vessels that are amenable to carrying and playing with the weight of thematic encounters. Saturated with pop culture references, industry emblems, and iconography imbued with meaning from his own life, WallowingBull forges convergent spaces to tell history and prophecy. Rather than shying from the complexities of futuristic envisionings of Native worlds, he problematizes the sterilized cleaving of Native peoples from the extraterrestrial, the otherworldly. He rejects not only terra nullius, but cosmic nullius. Here, it is clear, Native peoples populate the before, the right now, and the after, in this universe and the next.

Walking into Star WallowingBull’s studio on a dreary November Fargo evening was like entering a different realm. I sat down, locking eyes with four, larger-than-life red owls, their eyes swimming inquisitively across the surface of a canvas that roughly matched my height. They melted with what felt like collective intention, draining down to the lower right corner, their gravity threatening to grab and stretch my body and brain in the same direction. This painting, entitled Interdimensional Time Window is from WallowingBull’s series of the iconic Red Owl Food Stores logo that appears throughout this collection. Remembering back to 2004 or 2005 in his estimates, he described his journey to this particular iconography: desiring a visual landing pad that was as recognizable and ubiquitous with him as Andy Warhol was with Campbell soup cans. The warping, on the other hand, was also a warping of artistic influence. He reflected on his relationship with James Rosenquist, an artist WallowingBull both looked up to and learned directly from. Rosenquist, he articulated, was the one who inspired and encouraged him in this warping technique. The confluence of these prolific artists who interrogated and entertained the ethos of pop culture and advertising is clear, and yet, WallowingBull has infiltrated this approach.

In the Spaghettification of Minnegasco in Red Owl Sauce, the red owl heads are smeared to the point of disfiguration, while the former Minnegasco logo—an archetypal, cartoon Native figure adorned in a headband, dress, and blue flame (standing in as an adulterated feather)—floats in unflinching clarity. Minnegasco, as character, geo-cultural landmark, and reminder, seeps into the whirlpool of owls from the lower left corner, his flame-feather whisking into the abyss of red. It is in this intervention that WallowingBull amplifies and opens the convergence of these artistic influences. Minnegasco’s flame-feather spontaneously propagates throughout the sea of crimson, emblematic of WallowingBull’s artistic and intellectual morphing of traditions, praxes, and legacies. This is not a visual saturated in lament nor is it an exhumation of trauma. Rather, Minnegasco here is a vessel for potential: a self-repatriated figure imbued with new possibility, invigorated meaning. WallowingBull’s rendition of pop art is grounded in contemporary Native life and visuals—hijacking archetypal, commercialized, and commodified images of Native peoples as a way to incisively enact a Native present and presence and circumnavigate the stipulations of colonial time.

In this solo exhibition, one particularly acute demonstration of this enactment is in his most recent painting, Chief Bio-Dioxide. As WallowingBull and I shared laughter over his title, our conversation trailed into deliberations on representation. As he described, he is tired of the displays of Native life and people so commonly seen: incarcerated in the barren imaginary of fabricated and fantastical tradition, sequestered in a past inundated with colonial nostalgia. He explained further, this is not what he finds exciting to paint. Rather, he is drawn to the speculative, the cosmic expansion of Native life in all of its iterations to come.

Abstracted technological biomechanics compose this imagined, futuristic chief as he sits at a space bar, puffing at a crystal wine-stopper cigarette, another series of wine stoppers extending out as his war bonnet. His drink of choice? What is one to choose if not Red Indian Motor Oil. A vibrant circuit board hangs to the right, framed by a wasp and ladybug. To the upper left, Jupiter watches on from a distance, solemnly, in orbit (is Chief Bio-Dioxide at a bar on one of its many moons?). Belonging, space and place, time, and technology are teeming in contested, dialectical expansiveness. In this germinating future, WallowingBull interrupts the timelines imposed on Native peoples, perhaps swallowing and smoking them in a populated cosmos. Here, Native people are not discovered, are not stagnant subjects of a roving exploration. Instead, Native people are discoverers, are malleable, mobile, and agentive, embarking on voyage and odyssey, holding relationalities with circuit boards, Jupiter, motor oil, and insects. As comparative and critical Indigenous studies scholar, Vicente Diaz (2024) articulates, this “reiterates in radical modality the relationalities of kinship and reciprocal possibility between human subjectivity and other than human beingness, indeed, as the foundation for defining what it means to be human” (p. 4). The content of the painting lives in the quotidian but the intervention emerges from a quantum-infused novelty. The prevailing perspective and the temporal narrative of Native life is flipped upside down; though, WallowingBull might question: can anything be upside down in space?

How Diaz (2024) contends with framings of Indigenous stagnation comes into play here as well. As he writes, “Colonialism operates ‘discursively’, through discourse, and for our purposes here, the now familiar ways in which colonialism represents Natives in static ways…has precisely to do with very peculiar and problematic ways of conceptualizing Indigeneity in relation to place in the terms of movement and mobility” (p. 8). WallowingBull and Chief Bio-Dioxide reterritorialize colonial, cosmic cartographies through the disruption and disavowal of these discursive methods that thwart a Native transit of spacetime (applying instead the grinding death-drive of an eschatological timeline). While the imagery here may register as routine, it should certainly not be mistaken for the pedestrian. In fact, we may be demanded to ask: what is radically resituated, what topographies shift and fracture upon encountering a new dimension of the routine?

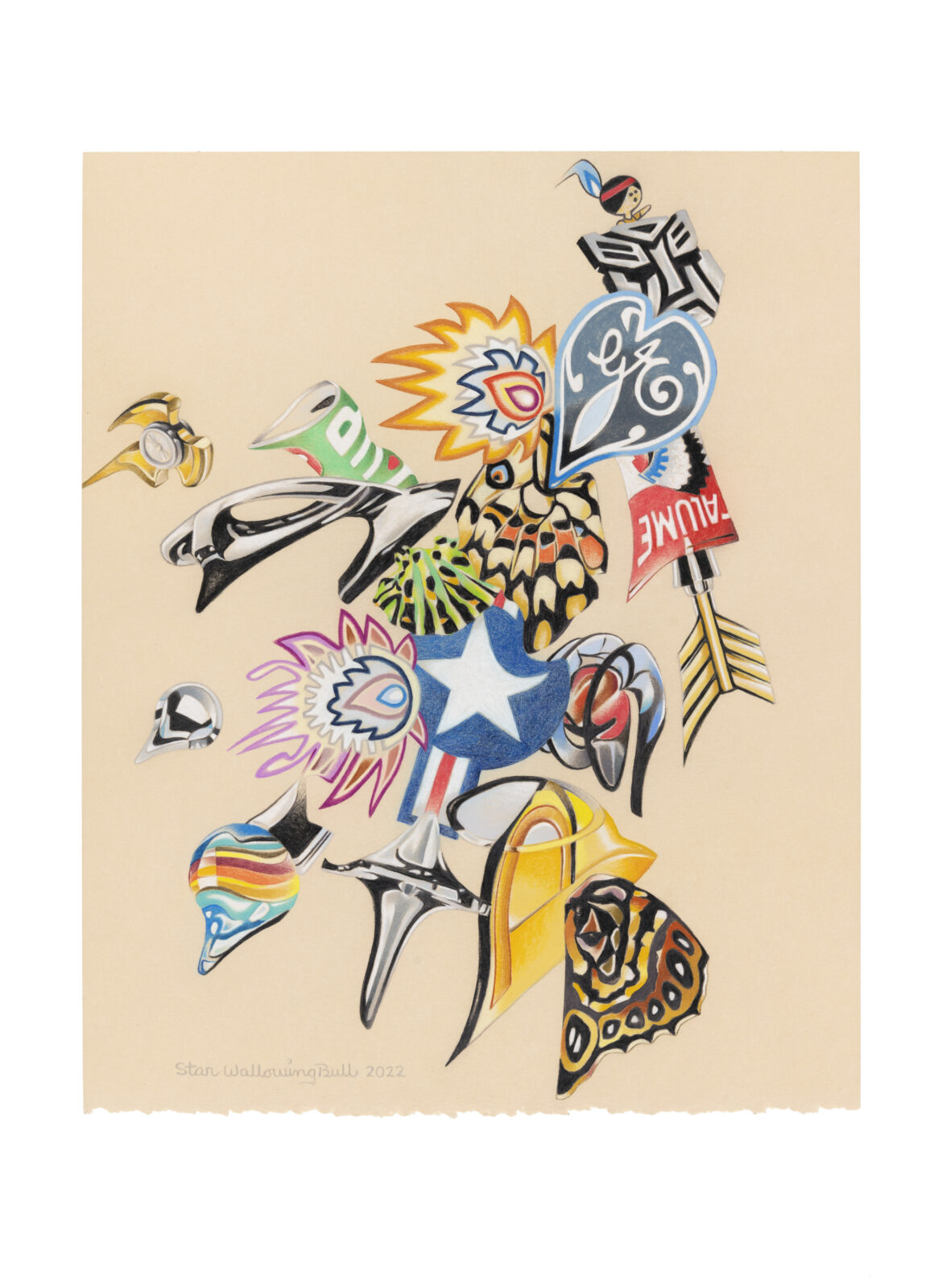

Throughout these works, the quotidian and the novel interweave in symbiotic kinship, proliferating windows that WallowingBull grants us access to: glimpses of these known and to-be-known worlds. In a smaller-scale, colored pencil work, Mechanized Chariot of the Gods, WallowingBull fashions a vessel (a receptacle to hold, a vehicle of passage) assembled out of parts both discernable and unidentifiable. Butterfly wings splice in and amongst chromatic, distorted machinery. A canister of Calumet baking powder (with its hallmark imagery of a red chief crowned in a headdress) and 7 Up serve as quasi-engines, propelling the chariot forth, intertwined with other distilled icons and visuals. While each facet of this humming, erupting chariot warrants consideration, their cohesive, collective form should not be dissected and promptly framed in individuated parcels, as if to taxidermy a rarity of evolutionary processes.

Minnegasco leads at the helm of this butterfly-chariot, hoisted by the head of the Transformers logo. His expression is one of awe as they traverse Eastward, subverting and filling the contrived void, this practiced myth of dearth and death. Figured as the passenger of the chariot, Minnegasco becomes the God, the one who is ferried across space and land, reforging an orientation to direction and place after being ideologically and materially cloistered to an exclusive trek Westward as empire leaked its hoarding, noxious tendrils across the horizon. WallowingBull’s deliberate collusions and collisions of material culture infused with trajectory express a vastness of time, a boundless, entangled possibility.

One blustery afternoon, I called up WallowingBull on a whim. I had been mulling over various angles in his work, listening on repeat to Willie Dunn, a Mi’kmaq folk artist who emerged to prominence in Canada during the 60s and 70s. Specifically, I had pressed repeat on the song “Pontiac” from his album: Creation Never Sleeps, Creation Never Dies. Dunn here references the Odowa leader, Pontiac, who in the 18th century galvanized a resistance against British presence in the region. Of course, Pontiac is now sewn into the popular imaginary as the supplanted Pontiac automobile brand. The song alludes to this, the sound of an engine sputtering to life inaugurating Dunn’s serenade. Nested here is a synchronicitous parallel that acts as a paradigm for WallowingBull’s body of work. Fully embracing these metabolizing maneuvers, WallowingBull metabolizes them himself, in turn regenerating a necrotic into a tonic, a dead end into a galactic highway, where (if we are lucky) we might spot Minnegasco piloting a mechanized chariot.

Both Mechanized Chariot of the Gods and Chief Bio-Dioxide inhabit what Mvskoke scholar Laura Harjo (2019) terms as “kin-space-time envelopes.” As she describes, these envelopes “function to unblock interactions typically fixed across spaces” (p. 28). The works instrumentalize themselves as a visual Draino, eviscerating the clogs of imposed demarcations, zipping past each set of eyes to the other Gods, the other bars, to Minnegasco’s kin and more, festering and fostering at the seams of a future unleashed from its confines. Of course, no kin-space-time envelope floats in the vacuum of space alone. Rather, these works in relational dynamism render what Harjo (2019) calls a kin-space-time constellation: “A kin-space-time constellation is a network of kin-space-time envelopes. A constellation then operationalizes multiple dimensions” (p. 28). Dimensions of the temporal and the spatial, the nostalgic and the bionic, the sacramental and the sacrilegious are rattling to a start (like a Pontiac car) as these works co-compose their constellations.

And yet, it is with Minnegasco—and other visual features of the mechanized chariot (General Electric’s logo for one)—and Chief Bio-Dioxide’s space bar, that the how of embodying and enacting the Draino-kin-space-time envelope (within the constellation) is elucidated. As Dakota scholar, Christopher Pexa (2019) explains: “despite the colonizers’ hopes, colonialism did not unfold as a monologue but rather in interactional and relational ways” (p. 41). What WallowingBull demonstrates here is that Native people are not simply subjected to archetypal imagery, but the subjects, allowing for a reacquisition, a commandeering, and repositioning of this imagery precisely through interactional and relational methods. The monologue disintegrates into a choir of speculation.

As he reiterated throughout our countless conversations, the entirety of this body of work is deeply inspired by his father, the Ojibwe artist Frank Big Bear. Familial kinship, memory, and home originate WallowingBull’s explorations. In another smaller-scale colored pencil drawing, Home, he aggregates and assembles symbols, icons, and other visual features of his childhood to construct a butterfly, flying in otherwise “vacant” space. The American Indian Movement emblem serves as the abdomen, the White Earth Nation license plate frames the upper right antenna, and East Franklin Avenue’s Street sign (a hallmark of the East Phillips neighborhood, an urban epicenter for Native communities in Minneapolis, and where AIM was founded) flanks the right edge of the butterfly’s body. It is in the East Phillips neighborhood where WallowingBull grew up. Here, fragments of visual memory and material vestiges of childhood map together to form this mutating butterfly, this living symbol of home. The butterfly, as a migratory, transitory, routed creature and relation serves as a reminder, a beacon throughout this body of work, that (as Diaz perpetually emphasizes) mobility is not the antithesis of belonging. Or, what Harjo implores: “It is crucial that we refuse a valorized narrative of fixity because we have not remained fixed in place” (p. 32). Repudiating valorization, instead, WallowingBull depicts a mobility that is derived from an ever-configuring constellation of belonging. He maps a metamorphosing, molting Homelands. A Terra Native. A Native Cosmos.

Diaz, V. (2024). Trans-indigenous Pacific Resurgence, Radical Relationalities and Subjectivities: An Introduction. [Manuscript in preparation].

Dunn, W. (2021). Pontiac [Song]. On Creation Never Sleeps, Creation Never Dies: The Willie Dunn Anthology. Light in the Attic.

Harjo, L. (2019). Spiral to the Stars: Mvskoke Tools of Futurity. The University of Arizona Press.

Pexa, C. (2019). Translated Nation: Rewriting the Dakhóta Oyáte. The University of Minnesota Press.