Beauty Is Medicinal: Dyani White Hawk on her Whitney Biennial Artwork

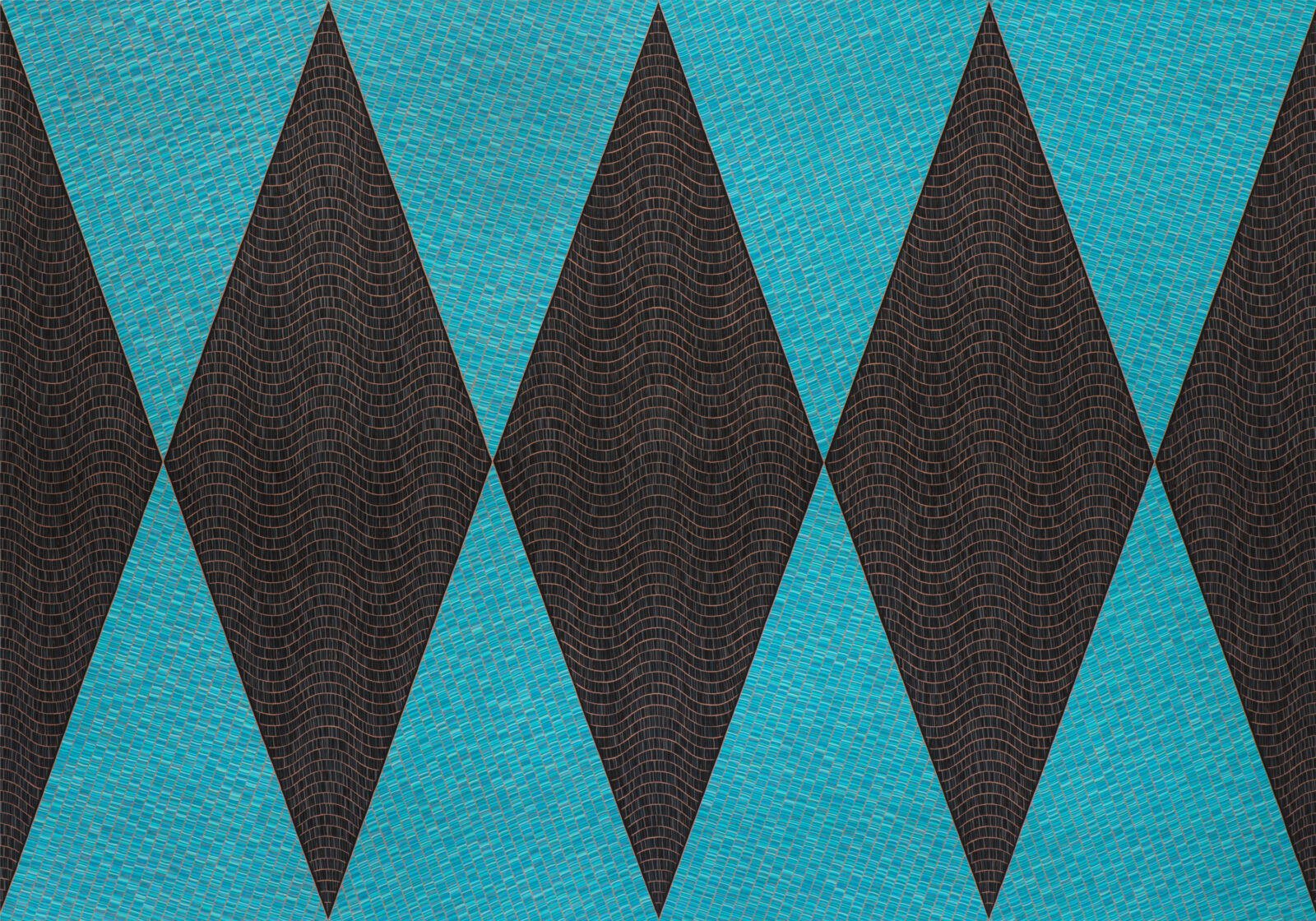

acrylic, glass bugle beads, synthetic sinew on aluminum panel

96 x 168 inches

photo by Ron Amstutz

For the 2022 Whitney Biennial, Dyani White Hawk wanted to make a statement. Her Wopila | Lineage (2022) delivers, resoundingly: comprised of more than a half million glass beads, meticulously applied over many months by a team of 20, it stands 14 feet wide and eight feet high, her largest work yet. But the messages aren’t about scale.

“No two ways around it, I wanted to position Lakota aesthetics in the Whitney Biennial,” says the Twin Cities–based White Hawk, one of only four Indigenous people in this year’s edition. “Native people have not been able to walk into public spaces and see our lives validated, reflected, honored, and uplifted in the way that other folks have. So they’re the first audience I want to address.”

But the work also offers welcome to Indigenous and non-Indigenous people alike—and the potential for healing.

“I genuinely believe beauty is medicinal,” she says in a new interview. “We all know that feeling when you stand in the beauty of nature, that awe and how it nurtures your soul, your spirit. Art can do something very similar.”

But she hopes beauty plays another role—as a lure to encourage visitors to linger longer. “Because if I offer this gift, they are more willing to stay longer and more willing to be empathetic to the harder parts of the conversation that are embedded in the work.” White Hawk’s art draws from influences including Lakota abstraction, Indigenous abstract practices at large, and abstract easel painting.

“I’m hoping to create opportunities for conversation,” she says, “around how connected those histories are and the fact that one doesn’t happen without the other.”

PSCongratulations on the Whitney Biennial! What thought processes did you have, knowing that you had access to this massive platform? Did it shift how you approached your work or—since Wopila | Lineage is your largest piece so far—how you think about scale?

DWH Yes and no. It’s one of the farthest reaching exhibitions in the country, so I definitely had thoughts about potential impact and what I might deliver to that particular audience. But at the same time, it definitely didn’t guide the work. If anything, it put a lot of fear in my heart about how the work might be received.

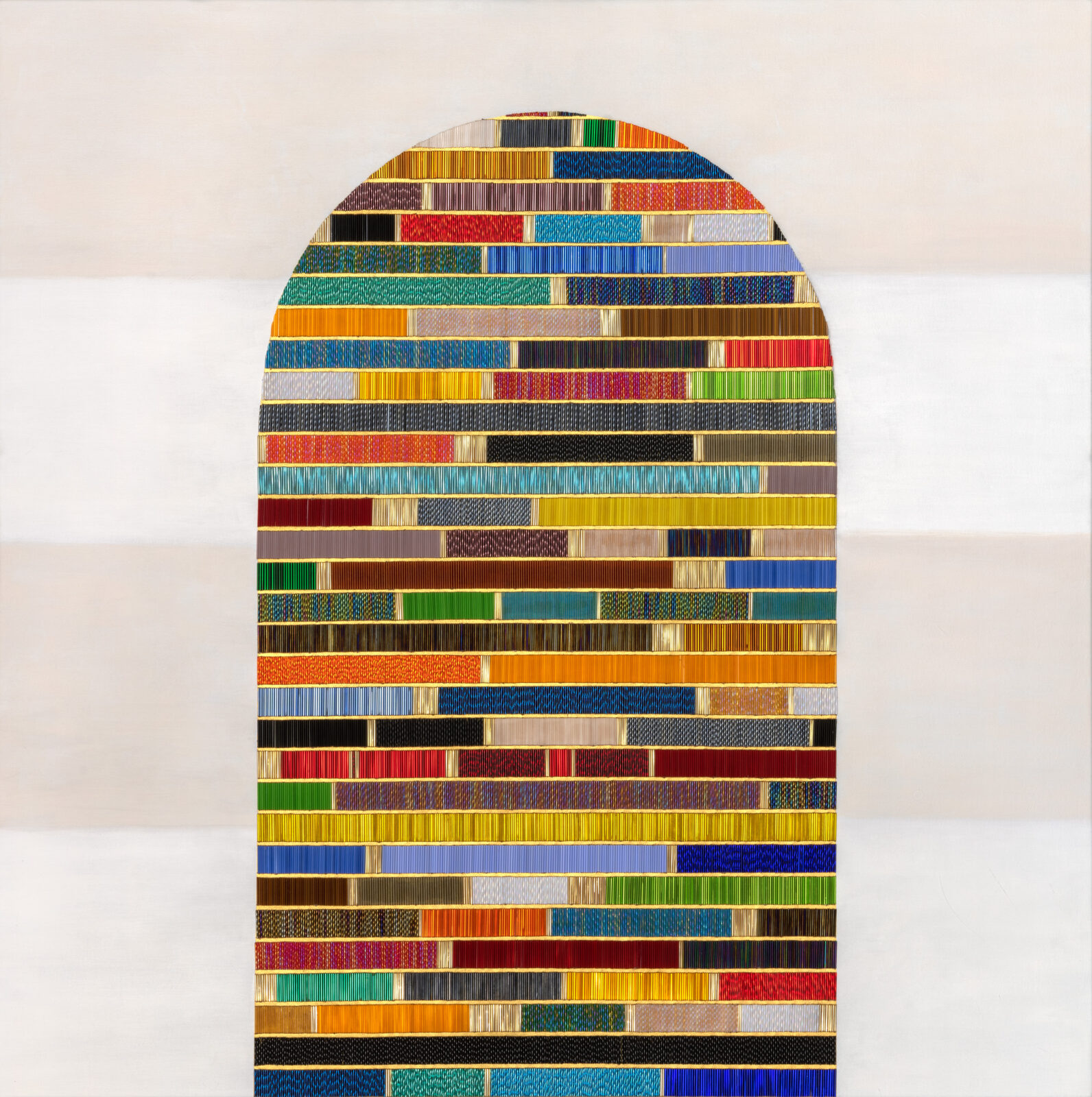

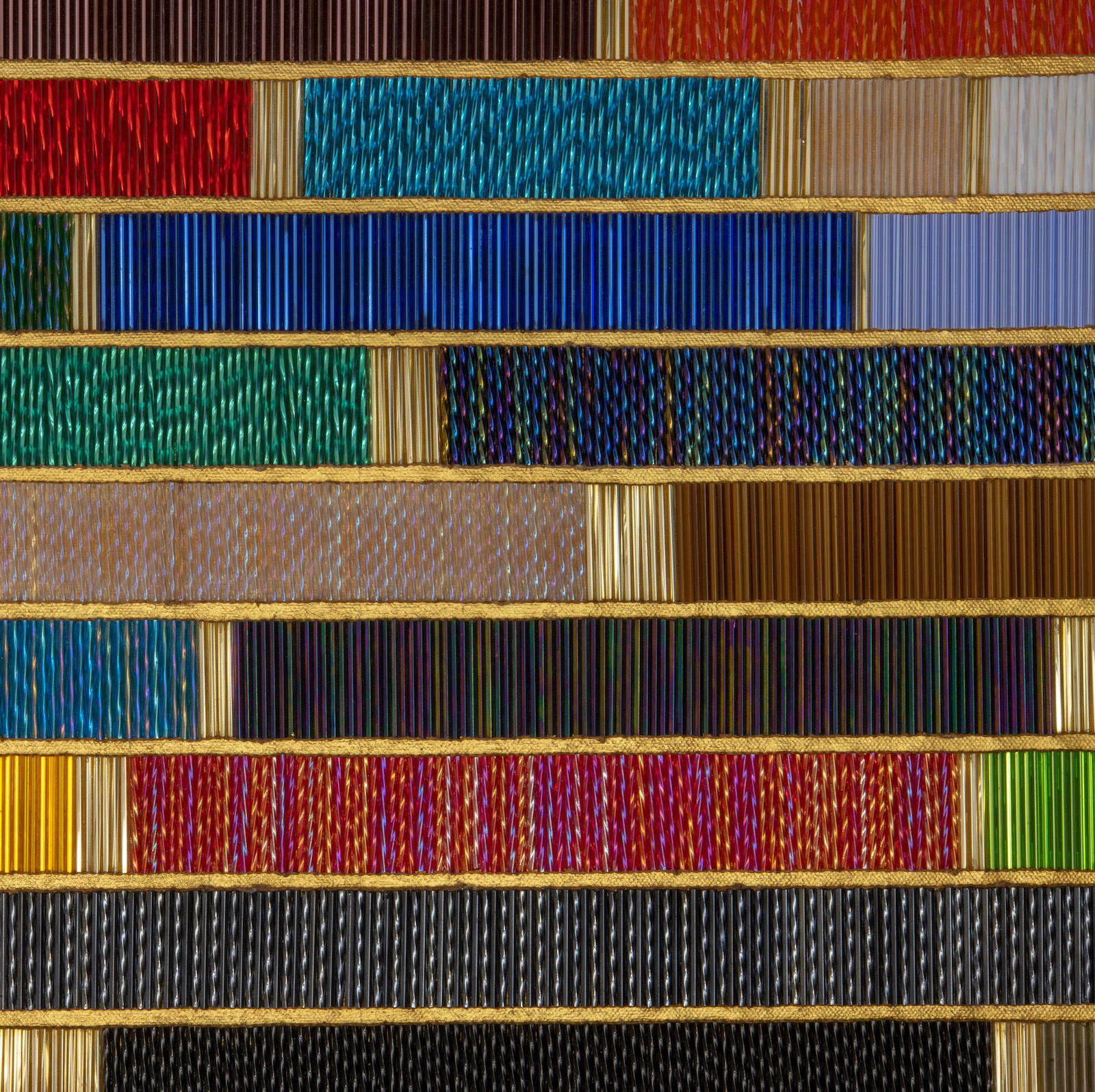

I had a meeting with the two curators, David [Breslin] and Adrienne [Edwards], the week before everything shut down for COVID. I had two pieces in the Armory Show: She Gives Quiet Strength VII (2020), a seven-by-10 foot painting and, to date, the largest painting I had made so far, and then, adjacent to that, a 48-by-48-inch, mixed-media work that incorporated painting and beadwork [Untitled (All the Colors), 2020]. Adrienne was enthralled with them both, and finally she pointed at the beadwork painting and said, “Could you do this”—pointing at the seven-by-10 painting—“like this?”

acrylic on canvas

84 x 120 inches

I remember laughing: “Yeah, but it would be a huge undertaking.” The painting took six months, and the last three months of the process were me working 70-plus-hour work weeks. Painting is faster than bead work, so translating something of huge scale into bead work at an even bigger scale was totally intimidating. But I’m talking to the curators of the Whitney Biennial and I’m definitely not going to say no!

So I sat down to create the composition. Once I came up with the design, I had a moment. During the thick of the beginning of COVID, I went to a cabin up north and started the bead work, and all of a sudden got hit with this profound fear: “It’s entirely possible that I could create this work and it will be passed by as ‘That’s nice. It’s pretty.’”

And I thought about it. This work is not on the surface overtly political—which has been the accepted and expected task of BIPOC artists in recent years. The media will eat up work by artists who spoon-feed education, so folks can walk up and be like, “Yes, I feel enlightened. I’ve learned.” It’s expected, it’s celebrated, and a lot of times those are the artists that are exalted because they’re giving you this education, which is absolutely necessary. But it’s right there on the surface and you can’t miss it. Artists that aren’t doing that super in-your-face work aren’t always as celebrated and supported.

Then I thought: BIPOC artists have not been afforded the luxury of making whatever the fuck they want—of making art for art’s sake. They’ve not been afforded the luxury of playing in their practice and then celebrated for it, not in the same way that European and European American men have been and are exalted for.

PS What did you do once you realized that was the source of your fear?

DWHI cried, because it felt scary and so unfair. I realized we’re all conditioned to these things through our experience in the world. My fear was an indicator that I, to some extent, had bought into it the idea that I needed to perform in a certain way to have my work cherished, valued, celebrated, honored. I felt like I needed to show up with the slap in the face.

I didn’t know if this work would do it, and I had to accept that fear and still do what I needed to do—and not buy into letting that push me towards some direction that I thought the world might be more accepting of.

My work pulls very directly from Lakota aesthetics, symbolism, teachings and spirituality, and worldviews. Those things are often embedded in the work in ways that people who are within that cultural practice are going to be able to walk up and see it. And it’s beautiful to see those things in public art spaces—to see your life reflected within that work.

But if you’re not already educated in those histories or aesthetic lineages, you’re going to approach it from a different lens, and then it might be fairly ambiguous. There’s some fear in doing this—“It’s so in-your-face Lakota!”—but at the same time I was like, hell yes. That’s what I want to do. No two ways around it, I wanted to position Lakota aesthetics in the Whitney Biennial.

That’s a huge gap: Native people have not been able to walk into public spaces and see our lives validated, reflected, honored, and uplifted in the way that other folks have. So they’re the first audience I want to address.” I want Native folks to walk in and be like, “Yay!”

PSOn the Whitney website you said you believe that “beauty is medicinal.” Some biennial visitors might come in, see your work, and just think, “Wow, beautiful.” Back to your initial fear: is beauty enough? How do you think about beauty?

DWHI’m totally okay with that. Beauty has a few different roles for me. I genuinely believe beauty is medicinal. It’s something we all seek out, we all crave. We look for it in our lives, in our relationships. We all know that feeling when you stand in the beauty of nature, that awe and how it nurtures your soul, your spirit. Art can do something very similar. When you walk in and you engage with that piece, it just gives you that sense of awe and that’s nurturing.

I also utilize beauty as a means to keep people in the conversation longer, because if I offer this gift, they are more willing to stay longer and more willing to be empathetic to the harder parts of the conversation that are embedded in the work. They have been offered this thing that fills them up, and now they want to hear more about it. It’s not aggressively shouting at them: “This is what you need to learn!” It’s more like: “Let me offer you this gift. And in return, let’s have this conversation where hopefully we learn more about one another.” Another tool of art is this ability to tell stories. And when we know one another more deeply, we’re more equipped to practice empathy and compassion.

PSTell me more about what they might take away if they sit with the work a bit longer. Lineage refers to the ways abstract expressionism was inspired in many cases by Native aesthetics, correct?

DWHExactly. So, “Wopila” expresses deep gratitude. And “Lineage,” like much of my work recently, is meant to honor and show gratitude for the lineage of Lakota women and their contributions to abstraction, for Indigenous women at large and their contributions to art on this continent, for the generations of practiced abstraction that helped nurture and guide the work of the Western artists that were inspired by their work and brought that back into their studios with them as they created easel paintings. In these pieces I’m pulling from those histories—from my own very specific history of Lakota abstraction, from Indigenous abstract practices at large, from abstract easel painting practices—and hoping to create opportunities for conversation around how connected those histories are and the fact that one doesn’t happen without the other.

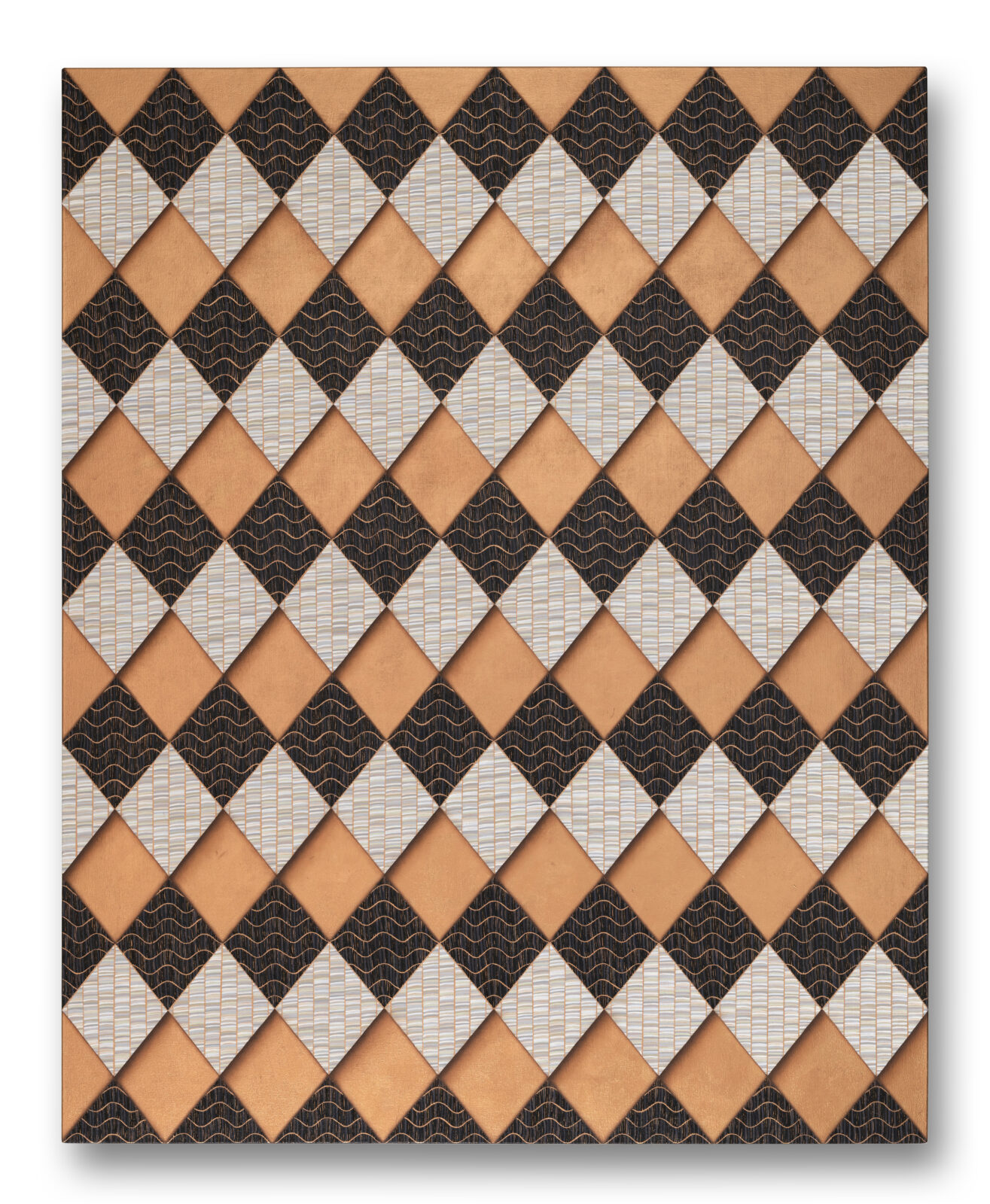

acrylic, bugle beads, thread and synthetic sinew on canvas

48 x 48 inches

acrylic, bugle beads, thread and synthetic sinew on canvas

48 x 48 inches

PS So this work isn’t only about your Lakota heritage; it’s a fusion of your own identities as a person of both European American and Native ancestry.

DWHTotally. I grew up in the city, but was nurtured within Native communities. I went to public school and I went to tribal colleges. I’ve studied Native art history and Western art history. So these works pull from my own experiences. They pull from our histories, and my hope is that they create conversations that allow us to start critically thinking about how art history has been taught and is being taught. And that we move towards models that are more honest.

PS And the thanks?

DWHIt’s an extension of gratitude for all the artists that came before us. We’re a link in that larger chain. I’m very grateful that I get to jump in now and play within that lineage. I’m grateful for all those forms of abstraction, and I think we can move towards healthier ways of acknowledging the value of them all.

It’s also gratitude for the community that made the work possible. This piece doesn’t exist without the people that helped me make it. Without the support of the McKnight Foundation, the Jerome Fellowship, the Academy of Arts and Letters, the Anonymous Was A Woman Award, and all the people who work in those spaces to fund artists.

Another thing I hope to talk about is that the notion of a singular genius in the art world is total bullshit. Nobody comes up in solitude. Everybody is a product of their environment. Everybody is inspired by people around them, by the art that came before them.

PS But there’s also a subversive element here, too—using a hallowed hall of contemporary art to critique the lineage of art history it has long championed.

DWHYes. It’s recognizing the bullshit that it has been, and the way that it’s been taught so far is extremely racist and sexist and ageist. Without a doubt, it’s a critique of how it has been presented to us and taught to us so far. But I don’t want to just sit in a place of anger. I want to sit in a place of: this is the BS that has existed; now how do we move towards a healthier future?

PS Is there also an element of addressing the white men who appropriated, or were inspired by, Native aesthetics and reclaiming abstraction: “Hey, we were here first”?

DWHColonialism is a beast that permeates everything, and it certainly permeates the art world and the way we teach art history. Were many of those men wonderful painters? Without a doubt. Were they gifted artists? Without a doubt. Were they singular geniuses that came up with it alone? No. The art world at that time was not recognizing the Indigenous artists from which these men drew inspiration, who were predominantly women, as artists. The people, and oftentimes even the specific cultures, they were looking at remain nameless in art history. And the credit of creative genius is given to the white male artist, speaking to their practices of collecting and looking at works outside of the Western “fine art” cannon, as opposed to recognizing the strength and agency of the works, and artists, they were inspired by.

digital photography installation

PS You’ve told the story of going to grad school for painting and feeling obligated to paint, but then missing the bead work you grew up with and feeling not entirely whole. At this point in your career, are you feeling fully present in how you seem to integrate all facets of yourself, from this form of making from your culture to your awareness of and response to ideas in contemporary art at large?

DWHYeah. That’s why it needs to keep happening. When I was at the Institute of American Indian Arts, I was taking painting classes and traditional arts classes, and I was practicing them all at the same time, but the paintings were painting and the bead work was the bead work. And then I learned quillwork while I was there, and my BFA show included all of those things.

But when I got to the University of Wisconsin, I got accepted into the painting department, and I thought, “Okay, I’m here to paint.” So the whole first semester I painted, but then I really started missing that other part of my practice. That is a part of me and I need it as much as I need the painting. So I had to figure out how to make them all happen at the same time and how to bring that part of my practice into the studio.

Before I was doing those things, but it was for cultural practice: making moccasins for dancing, making leggings for dancing, making a dress for myself or my daughter to dance at pow wow or ceremony. So a functional use, specific to cultural practice. I had to figure out how to bring those practices into my studio practice so that I could fulfill the desire for all those things to happen all the time. And then I’ve been doing it ever since.

PS The logistics around this piece must’ve been complex. You had 20 people helping and beads sourced from all around the world?

DWHTwenty people helped, 18 people beaded. There are over a half million beads—close to 570,000 beads—on the piece. I had to buy way more beads than that to find all the right ones. The two companies that produced the beads are both Japanese bead companies, so some came straight from Japan. Some were in the States. And then to get enough of each of the colors, I had to find little stashes that were owned by either stores or individuals all over the place: Russia, California…

PS For me, raised Catholic, I see a similarity to rosary beads and the repetitive nature, which is part of many spiritual practices, of that particular form of prayer. Are there the ritual or spiritual aspects to making this kind of work?

DWH I don’t want to romanticize it, because that has all too often been the pattern when non-Native people inquire about Indigenous spiritual practices. But yes, because this work is rooted in Lakota artistic practices, the approaches to the work are guided by cultural value systems. Even in choices around who I brought into the studio to help. Out of the 20 folks who helped, three were non-Native, but before they came in I had talks with them about values in approaching the bead work, because historically that making comes through supporting your family and your relationships. Like, if you’re making a pair of moccasins for somebody, you’re making that with love and you’re gifting that to them. And because of that, you’re very conscious about where you’re at when you’re making that thing. We’re taught you don’t sit down and do this while you’re angry. Your intentions go into that work.

So when we had brought in folks that were non-Native, I sat down and talked to them about those things. I’m not trying to convert them into our spirituality, but I want them to know that when you’re in this space, when you’re working on this work, you’re sober. When you’re working on this work, you work on it when you’re in a good head space. If you’re not in a good head space, you don’t work on it.

That has carried through into my studio practice. So we routinely smudge here. There’s prayer that goes into this work and expectations that the folks who are helping me are bringing those teachings and those value systems into the piece because we know that the art goes out into the world and then does its work. It’s now over there doing its work.