Bockley Gallery is pleased to welcome Natalie Ball (Black, Modoc, Klamath), Grace Rosario Perkins (Diné/Akimel O’odham), and Eric-Paul Riege (Diné) for the group exhibition, Now You See It, Now You Don’t, featuring new and recent works in painting, sculpture, and video.

The exhibition’s title is borrowed from the magician’s mouth—a phrase that signals temporality, performativity, and spectatorship around an act of showing and telling, of seeing and not seeing from one “now” to another, and the celebrated enjoyment of unknowability within the audience experience.

The particular visibilities in the exhibited works carry intentionally unseen accumulations of material density as well as the artists’ experiences of time, ancestors and relatives, labor and language, love and grief, politics and violence, memory and place, and more. Individually and collectively, they contain ways of world-making that determine the what, how and when to make visible, and especially the choice to do both at the same time.

Natalie Ball

Through assemblage, Natalie Ball’s autoethnographic practice activates lineages within Black Abstraction and Indigenous ceremony that channel ancestors while reflecting her lived experience, including as a future ancestor. Through found, hunted, gathered, purchased, and gifted materials infused with multivocal past lives and meanings, Ball creates, in her words, “a visual archive of where and who I come from.” Seeking to disrupt essentialist forms of the truth with a truth, Ball complicates how materials and their treatment shape expectations around “looking Indian” and “seeing Indian.”

Combining the synthetic and the natural, living and undead, urban and rural, as well as elements from popular culture and ceremony, Ball’s materials become dissembled, commingled, abstracted, and reinvigorated into newly agential, expressive objects akin to Power Objects—a term used to describe shared cultural symbols or objects used in ceremony. While the memories, knowledge, and agency within Ball’s sculptures are known to their many makers and communities of belonging, Ball offers them as proposals: in her words, “I am not trying to teach or learn you.” Ball’s sculptures hold their own power and ask you to feel it.

With her Pussy Hat series of free-standing sculptures, Ball reacts to the 2017 march for women’s rights in Washington, DC, by making her own version of the movement’s symbolic garment, which by that time millions of women globally were donning thanks to an open-access crochet pattern for pink hats. Pussy Hat (2018) is a double protest in that it wildly critiques the movement’s points of privilege and exclusionary follies while remaining aligned with feminist activism’s power to rage. Further, it asks: who is allowed to protest peacefully?In Wedding (2019), from her post–graduate school series Bad Lucky Indian, Ball began materializing the complex question: “How are we wedded to expectations around self-determination, including if we don’t self-determine?” An amalgamation of her thoughts around tribal membership, Pan-Indianism, blood quantum, and other ideas are folded into rough-cut and caringly stitched textiles that create portals and patterned color fields, behind which figuration seems protected from view. Tucked under Pendleton and Hudson Bay Trading Blanket family heirlooms and a gifted wedding quilt, a head of braided hair and woven cedar looks away, and a bare pair of pine pole legs stand on the ground.

Grace Rosario Perkins

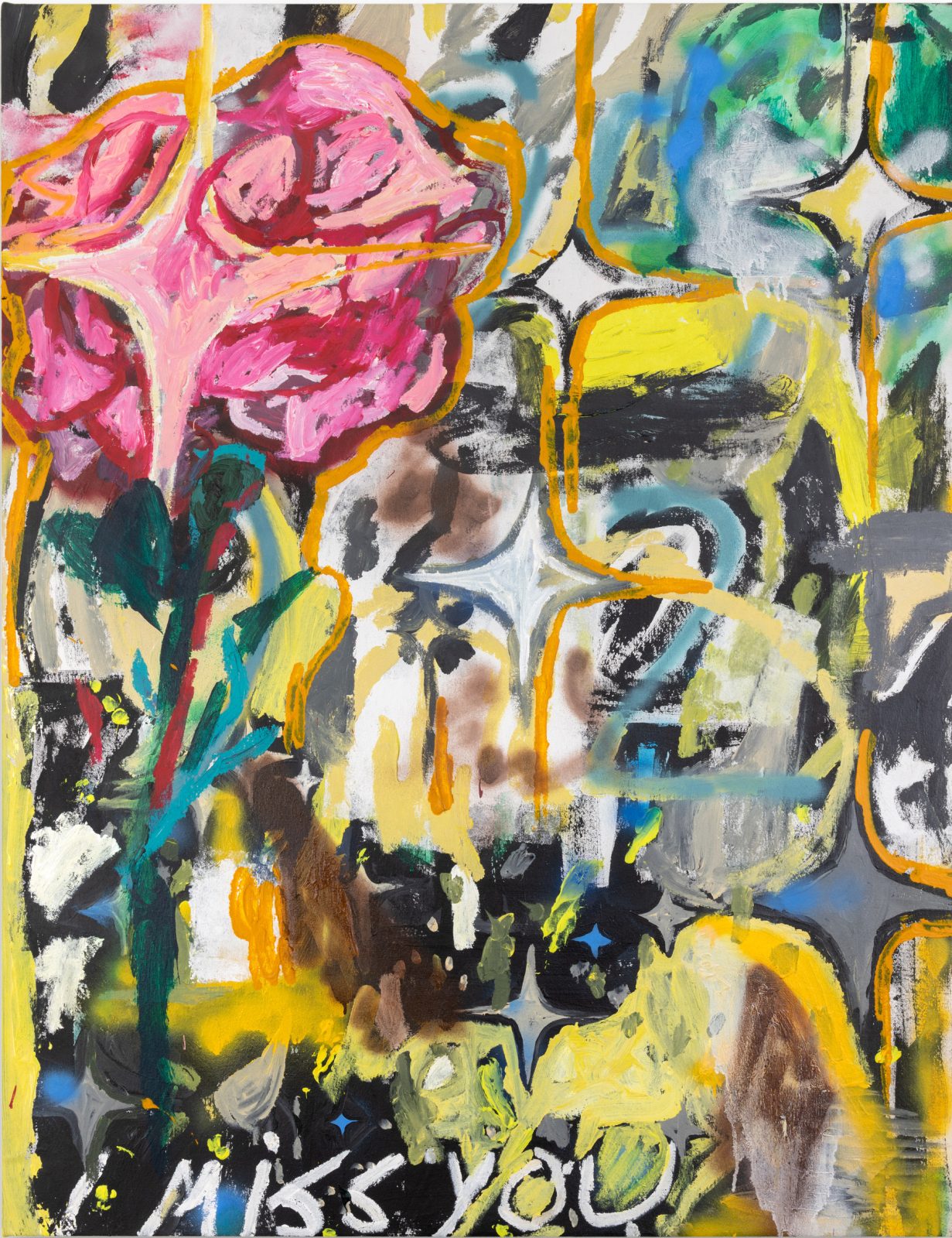

Channeling intuition, family, ritual, and magic, Grace Rosario Perkins’s paintings conjure the autobiographical. While she has referred to her practice as pictorial storytelling and scenographic placemaking, she refuses any legible visual narrative or view. To Perkins, materials are images, even if they are unseen. Her gestural, layered, and maximal surfaces carry her negotiations between adding and subtracting symbol-rich color and imagery.

Perkins aims to subvert preciousness through her material and display choices. Working with enamel and acrylic paint, found fabric and language, and Xeroxed photographs, her underpaintings are often totally redacted. Allowing her intentions to change throughout a work’s becoming, her paintings are, in her words, like “journals, records of fleeting moments.” Perkins variably installs her paintings as a nod to traditions of signage: suspended, wall or floor based, with or without stretchers and frames.

See, If You Believe That You and Me Can Change the World Someday (2023) carries lyrics from the 1990s–2000s R&B women’s group 702, which Perkins has redacted with an inverted sun, abstracted traces of her current study of Indigenous plant knowledge, and her recurring iconography of the spider’s web. An encompassing metaphor for the artist, Spider Woman honors the Diné creation story, and expands ideas of protection, mobility, agency to make and remake home with one’s body, interconnectivity, stickiness and entrapment, resilience, and more. Many of Perkins’s works are homages to specific family members. Within the large spider’s web that dominates Mom Jokes to Make Her Hair Curly Like a Sheep (2022) is a relatively small Xeroxed photograph of the artist’s mother as a teenager holding her cat outside their family home. Perkins speaks with intention around infusing her materials and subject matter with love, compassion, care, and sweet things. The atmospheric painting, The Landline is Disconnected But She Still Knows How Big It Is (2023), was made for the maternal grandmother who raised her and who recently moved from their intergenerational home of more than fifty years to a care facility. Symbols like a pink carnation, stars, the words “I MISS YOU” in handwriting copied from a stranger’s graffiti, and the phone number attached to the home’s disconnected landline speak to imaging the grieving of a loved one who is both here and not here.

Eric-Paul Riege

Eric-Paul Riege’s practice in soft-sculpture and durational performance engages, honors, embodies, plays with, and balances the artist’s lived experience in relation to ancestral traditions in weaving and adornment, especially those passed down from his maternal family. As both a carrier and protector of knowledge, Riege creates new forms within the Diné (Navajo) worldview of hózhó, which encompasses the values of beauty, balance, and goodness in all things seen and unseen, in physical and spiritual realms.

Like Ball and Perkins, Riege’s media traverse low and high, precious and non-precious: wool, faux fur, polyester, horse hair, synthetic hair, cashmere, tin, and others. Keenly interested in perceptions of authenticity, especially what is perceived as authentically Native American, Riege notes that what is less seen in time and space—what is decayed and has lost pigment—is often considered most authentic. Subverting this ethnographic entrapment, the gentle tonal range of the artist’s color palette honors birth and life. Blacks, browns, and beiges approximate human skin colors and the hair of churro sheep, a sacred animal to Navajo communities whose population was nearly decimated by the US government in the 19th and 20th centuries in an effort to destroy Navajo livelihood.

Diné weaving shares in common a barely noticeable material opening or woven line that serves as a pathway to futures for Spider Woman, the creator. Inhabiting this animacy in his work, Riege further considers his sculptures living beings and ,thus, ever-changing and changeable over time. The small torso-sized soft sculpture, |||||||| (2023), is woven upon dah ‘ístł’ó {loomz (2019), combining elements of existing sculptures with new parts, notably a loom-beaded frontal plate. Often working in durational performance to activate his sculptures, his new video, Tender kagí horse hair skin (2022), shares a documentary, ceremonial, and world-making tone in which the sonic is also foregrounded.

Riege’s sculptures often play with scale, space, and gravity to mimic and abstract the technologies and forms of looms, patterns, and jewelry. jaatłohYe’iitsoh [13-14] (2023) belongs to the artist’s ongoing series of large-scale “earrings.” Hung in the gallery’s two front windows the works are allowed to perform precious encasement while remaining animate as they gently turn and sway with gravity. The pair’s lush, white, central medallions are coiled in the tradition of Diné baskets, and they carry cascading adornment. Stuffed and hanging spider leg–like forms are further tiered, and black fringed ends are wrapped in tiny, metal cones used as sound and meaning-makers within many regalia traditions. Riege sees them as “floating, ghost-like, not static but still, like our sleeping state—air is part of this state, moving and being moved.”

Artist Biographies

Natalie Ball (Black, Klamath, Modoc) received a bachelor’s degree with a double major in Art and Indigenous, Race & Ethnic Studies from the University of Oregon. She furthered her studies with a master’s degree focused on Indigenous contemporary art at Massey University in Aotearoa (New Zealand) and an MFA in Painting & Printmaking from Yale School of Art. She is the recipient of the USA Fellow Award (2023), the Ford Foundation’s Hallie Ford Foundation Fellow (2020), and a Pollock-Krasner Foundation Grant (2019), among others. Ball’s solo exhibitions have been held at the Rubell Museum, Miami (2020) and the Seattle Art Museum (2019). Group exhibitions include at Sharjah Biennale (2023); Oregon Contemporary, Portland (2021); UTA Artist Space, Los Angeles (2021); Berkeley Art Center, Berkeley (2020); Vancouver Art Gallery (2019), and SculptureCenter, New York (2019). Her work can be found in institutional collections including the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Seattle Art Museum, and Forge Project Collection. Born in Portland in 1980 in Portland, Ball lives and works in Chiloquin, Oregon.

Grace Rosario Perkins (Diné/Akimel O’odham) is a self-taught painter who spent 15 years as an arts educator and most recently served as associate professor of Painting and Drawing at Mills College in Oakland, California. Some recent sites of engagement include MOCA Tucson, Cushion Works, ONE Archives, Residency Art Gallery, the Oakland Museum of California, Mills College, Cooper Union, the San Francisco Art Institute, and the University of New Mexico. Perkins has been nominated for a United States Arts Fellowship and SFMOCA’s SECA Award. Born in Santa Fe in 1986, Perkins lives and works in Albuquerque, New Mexico.

Eric-Paul Riege (Diné) holds a BFA in Studio Art and Ecology, with a minor in Navajo linguistics, from the University of Albuquerque, New Mexico (2017). His recent solo exhibitions include Hólǫ́llUllUHIbI [duet] at the Hammer Museum (2022–2023); Hólǫ́—it xistz at ICA Miami (2022), and (my god, YE’ii [1-2]) (jaatłoh4Ye’iitsoh [1–6]) (a loom between Me+U, dah ‘iistł’ǫ́ at Bockley Gallery, Minneapolis (2021). Recent group exhibitions include the Toronto Biennial of Art (2022); Prospect 5: Yesterday we said tomorrow, New Orleans (2022); and SITElines Biennale by SITE Santa Fe (2019). Riege’s work is in the collections of Forge Project, ICA Miami, and LACMA, among others. Born in Na’nízhoozhí (Gallup, New Mexico) in 1994, Riege lives and works in Na’nízhoozhí.

Artist Conversation: Thursday, March 2, 5 to 6 pm

Opening Reception: Thursday, March 2, 6 to 7:30 pm

acrylic and spray paint on canvas

54 x 35 inches

acrylic and spray paint on canvas

54 x 41.5 inches

cashmere, sherpa, faux fur, muslin, polyfil, cotton, churro sheep yarn, tin jingles, synthetic fringe, PVC pipe, rope, metal rings

approximately 103 x 40 x 12 inches

churro yarn, Navajo warp churro yarn, foam, muslin, ask ink traces, glass beads, PVC pipe, synthetic fringe, metal ring

36 x 14 x 4 inches