An Expanding Landscape: George Morrison

wood

60⅛ × 168½ × 3 in.

Collection Minneapolis Institute of Art. The Francis E.

Andrews Fund. © Estate of George Morrison/Briand Morrison

The first time I saw an artwork by George Morrison was 2015. It was the day before my interview at the Minneapolis Institute of Art, and I had never set foot in the museum, so I went to explore. I walked up the grand stairway that leads into the museum’s original building, designed by McKim, Mead, and White, passed friendly greeters, turned right, and wandered down a long hall before turning to enter a gallery. It was the first of a suite of spaces devoted to Native American art and I chose it at random. What I encountered in the space would shift my consciousness. It resulted in new friendships, expanded networks, and meaningful connections. It deepened my curatorial practice.

What set this transformation in motion was a large wood piece, Collage IX: Landscape (1974) by George Morrison. It took up the entire east wall of the gallery, where it quietly commanded attention. While massive, it is not ostentatious. Though it is colorful, the eye needs time to adjust to its rhythm and nuances before a full appreciation of its chromatic range develops. Titled with a reference to nature, that connection is revealed slowly and then thrills with its organic rhyme. Morrison clearly assembled its parts in a specific order, but the materials seemed simply presented, selected because of their individual character. Where did he intervene with his hand? It was not possible to see. The scale and its unity, the confidence and ambition- everything combined to make me say out loud, “Who did this? What is this?” I felt a delight in being surprised, being re-enchanted with creativity, and amazed by something extraordinary that had been brought forth, had not existed before Morrison made it.

I was surprised to find that Morrison was born in 1919, making him part of a generation I have spent a lot of time with as friend and art historian. As I learned more about Morrison’s career, his work, his friendships, and his deeper connections in the world, I kept muttering, “How did I not know about him? Why did I not know about him?”1 It turns out I had heard a little about him, since he appears briefly in Ann Gibson’s Abstract Expressionism: Other Politics (1999). But what I experienced in the gallery erased the modest reproductions in that book from my mind and refocused me on truly seeing Morrison. It also shifted me immediately into asking, “Who else do I not know about? Who are the other Indigenous modernists? How did Morrison and his contemporaries think of identity in relation to art? Did they fight against it, embrace it, or was it complicated?”

Of course it’s complicated, because human beings are complicated. Morrison often said he was an artist who happened to be Indian, not an Indian artist. At the time of a huge exhibition of historical Native American art in Minneapolis, Morrison told the Minneapolis Tribune, “I have never tried to prove that I was an Indian through my art. … Yet, there may remain deeply hidden some remote suggestion of the rock whence I was hewn, the preoccupation of the textural surface, the mystery of the structural and organic element, the enigma of the horizon, or the color of the wind.”2 What Morrison conveyed was a sense that place matters. Where you come from physically, historically, and where you are spiritually. It is in you and you are part of it.

This was a rare reflection on that relationship for Morrison. It came in the wake of the 1968 founding of the American Indian Movement (AIM) in Minneapolis and his own 1970 return to the Twin Cities after many decades on the East Coast. Born in Chippewa City in northern Minnesota, this return to the region would inspire his last three decades of work. Morrison had earlier considered himself an artist—in response, perhaps, to being considered “not Indian enough” to be included in exhibitions organized by Native arts organizations or defined first by his heritage in an art world prone to boxes, bins, and labels. By 1972, in the wake of multiple parallel civil rights efforts that included AIM, Morrison may have started to understand how embracing that part of who he was did not mean reducing himself to a label, but rather could be an expansion of his own understanding of the ways he navigated existence.

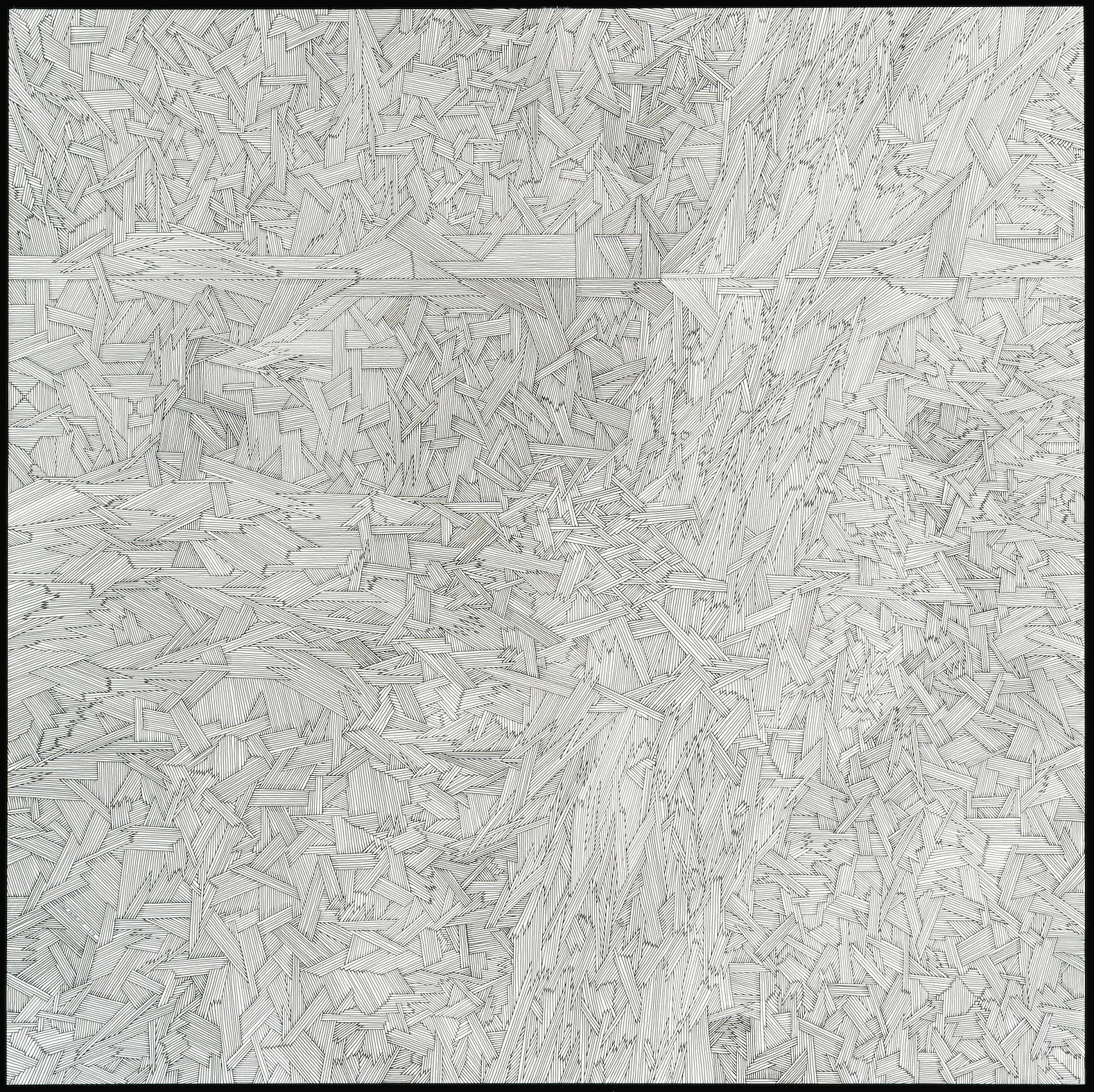

Collection Walker Art Center

Later in life, after many health challenges, Morrison accepted two names, offered through a healing ceremony given to him by a cousin, Walter Caribou. These Ojibwe names were Wah-wah-ta-ga-nah-gah-boo (Standing in the Northern Lights) and Gwe-ki-ge-nah-gah-boo (Turning the Feather Around). Having these names presented to him in ceremony by an elder meant a lot to Morrison. In their evocation of landscape and sky, they underscored the continual source of his vision—the north shore of what the Ojibwe call gichi-gami or Great Sea (Lake Superior)—and the underlying image in Collage IX: Landscape. The great lake is the fundamental reference point for Morrison in so much of his work. It grounds him in life and in his relationship to the cosmos and to creativity. Its horizon line, often in the top third of a drawing, painting, or wood piece, is the charged place where everything touches. It appears in unlikely places, as in meticulously crafted ink drawings where lines dazzlingly proliferate in a manner of weaving, but allow for that calm edge to run across as a horizon, as when waves crash and reveal it in the distance.

Standing on the shore of Lake Superior, it is easy to feel as though you are at the edge of a sea. It is massive, formidable, ever-changing, gorgeously terrifying, mysterious and glorious. It is the largest freshwater lake in the world by area and third by volume. Its deepest recesses go below thirteen hundred feet. Storms can swell its waves up to thirty feet high, and some intrepid Minnesotans surf these waves. In winter. The rocks on its northern shore are endlessly fascinating, compulsively collectable, and they date back billions of years, to the earth’s early prehistory. Morrison’s ancestors were the first human inhabitants of the area. No wonder this natural wonder is central to his work. But it isn’t just this vast sea, it’s the entire environment around, affected by and affecting the water. And no matter what colors or textures erupted in the environment and despite the distinctive character of the seasons—the horizon was a meaningful place to focus his gaze:

Every moment, the horizon is present. The horizon has been an obsession with me for most of my life. It makes an indelible image that, for me, stems from being born and growing up near the edge of the lake. Later, spending many summers on the Atlantic shores reinforced it. I think of the horizon line as the edge of the world, the dividing line between water and sky, color and texture. It brings up the literal idea of space in a painting. From the horizon, you go beyond the edge of the world to the sky and, beyond that, to the unknown. I always imagine, in a certain surrealist way, that I am there. I like to imagine it is real.3

acrylic on canvas

30 x 60 inches

Collection Minneapolis Institute of Art

Morrison started these “wood paintings” in 1965, while in Provincetown, Massachusetts. He was thrilled that the driftwood that washed up on the Atlantic shore came from “the South Seas, the Caribbean, the North Atlantic. It all washed up on this tip of Cape Cod. Some had bits of paint, half worn off. Some had rust stains or colors soaked in. Industrial boards were washed nice and gray. Nail holes added texture and color where rusted nails had oxidized the wood. There was an interesting history in those pieces who had touched them, where they had come from.”4 Morrison and his children and friends’ children began collecting it. People who saw his first attempts began collecting and sending him pieces. Collage IX: Landscape represents connections in the world, relationships between shores, nature and the artist, chance and deliberation, things that escaped their borders and traveled on the waves to him. Pieces of former trees that friends saw and thought to pick up and send to him.

He devised them from scratch, out of his head—an automatic, improvisatory process comfortable to him. In his earlier paintings made with no aim of recognizable imagery, Morrison took care to assemble the necessary components (or had a vague starting point in his mind) and then worked spontaneously over many hours in a single night, exploring the possibilities of paint to suggest images rather than depict tangible things. “I was trying to capture an inner thing,” he recalled of paintings like Untitled (1960), “where you began with the act of painting itself, then images began to emerge. Almost like subconscious painting.”5 For the “wood paintings,” he allowed a deliberate reference to landscape and a horizon line, but carefully considered the information each piece brought to the whole. “The driftwood itself gives a sense of history—wood that has had a connection to the earth yet has come from the water. I realize now that in making these, I may have been inspired subconsciously by the rock formations of the North Shore.”6 This reference to stones is evident to anyone who has visited Lake Superior’s north shore. Morrison’s varied sizes of wood often look like mineral deposits, pebbles embedded in boulders, the crevices that hold them shaped and revealed by millions of wave crashes on their surfaces.

Collection: Minneapolis Institute of Art. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. John Weber.

© Estate of George Morrison/Briand Morrison

Seeing Morrison’s work and learning who he was became a way in to a new place for me. He provided an opening, a revelation, and a path to new narratives and ties in what became my community. Following that invitation to know Morrison has expanded my practice, my humanity, my connections where I am. I have devoted myself to learning the history and the cultures that come together in Minneapolis, the deep histories and those that are raw, just under the surface. That is what Morrison has brought to me. Where he has led me. The new relationships I have with makers here, Indigenous and not, is a means to respect where I am, to learn from it and to be an advocate for what is good in it. The opportunity to be present here has reinforced my conviction that the narratives I always bristled against were fundamentally untrue, were hiding things. There are perpetually more reasons to poke and prod and dig. Those invitations come to me, as clear as spoken words, from artwork itself.

Place has been a fundamental teacher for me in each of the places where I have lived and made deep connections: Chicago, Madison, Philadelphia, Minneapolis. I have valued these lessons and those who have been the agents of new knowledge, new perspectives, living and in spirit. It’s up to me to put that into practice, to have faith in what has been revealed and to be the agent of change with and for others. It is a partnership across time, across differences, a recognition that we need to collaborate fully, to speak without fear in support of new narratives. This is fundamental to art history and to being a curator.

For more on why such questions continue to arise, see Robert Cozzolino, “Claiming the Unknown, the

Forgotten, the Fallen, the Lost, and the Dispossessed,” Panorama 2 (Fall 2016), https://editions.lib.umn.edu/panorama/article/robert-cozzolino-patrick-and-aimee-butler-curator-of-paintings-minneapolis-institute-of-art.The exhibition was American Indian Art: Form and Tradition, jointly presented by the Walker Art Center

and Minneapolis Institute of Art in 1972. Morrison quoted in the Minneapolis Tribune, October 22, 1972.George Morrison and Margot Fortunato Galt, Turning the Feather Around (Saint Paul: Minnesota His-

torical Society Press, 1998), 192.Ibid., 125.

Ibid., 111–112.

Ibid., 128.

Robert Cozzolino is the Patrick and Aimee Butler Curator of Paintings at the Minneapolis Institute of Art. This essay is reprinted, with permission, from the volume The Unforgettables: Expanding the History of American Art (Oakland: University of California Press, 2022), edited by Charles C. Eldredge.