Just Friends: A Conversation with Maggie Thompson

My first visit to Maggie Thompson’s studio in Northeast Minneapolis’ Northrup King Building was spent on our feet, moving between multiple looms and a fitness pole to the various stations where new works were becoming. The second visit was all sit-down—a time to sound some lingering resonances from the first. This written version commingles these visits with some follow-up DMs and afterthoughts. The occasion of it all was Just Friends—Thompson’s first solo exhibition at Bockley Gallery (July 24 – August 27, 2022). Technically a silent show, the sonic surfaced throughout our exchange, which made me think of this conversation as a kind of backstage pass, and not only to the ideas and processes in the studio before the event of the exhibition.Due to the exhibition’s motivations—five intimate works that process the connections, depths, and aftermaths of love—this conversation naturally became a kind of rehearsal in feeling in public. I learned quickly on our feet it wouldn’t be any other way with Thompson, at least for now, and for that I am grateful.

EGAs your practice is so tactile and invested in experimentation, I thought we should begin the conversation in and from the perspective of the studio. Lots of labor and time bring the materials and verbs of your practice into relation and give them meaning, often through many hands and hearts in collaboration with yours. There seem to be a couple assistants here regularly, and your new-to-you, tall-as-a-table Great Dane, Winston.

MTI like working with people, and I enjoy mentoring—some assistants are artists in mentoring programs, and some stay on to work regularly in the studio after the program ends. My friends help, too. And Winston: he’s kind of saving my life these days, literally.

EGThere’s currently a lot of testing going on, of materials, scale, color, texture, structure. There’s measuring, cutting, stringing, sifting, stuffing… what other verbs?

MTSewing, talking. Processing…

EGThere are fabric bolts and smaller yardage, glass beads, clear vinyl, various brands of breadcrumbs, vellum, photographs, thread. The studio has a DIYness and modularity that feels just as intentional as the refined skills of your practice. Like when your friend Tim was concocting a breadcrumb-sifting system for a sculpture by pairing a light stand, metal clamps, and a piece of US letter-size paper. All feels unpredictable in a good way.

MTSo far, I don’t work in series, and in general I don’t work in the same way very often either. Each work is usually really involved and connects to something very specific that’s personal to me. So the space does need to adjust to each idea, each work.

Also, back to the verbs in the studio: listening is another verb. We’re always listening to music.

EGWhat’s playing recently?

MTI make soundtracks around periods of time. The recent one is called “Ducks.” All love songs, in different ways: “The Mess Inside” by the Mountain Goats, “Bite Me” by Avril Lavigne, “Closure” by Taylor Swift, “He Don’t Love Me” by Winona Oak, “The End” by The Lower 48, and many others. Music is a really important part of going through the emotions of making work.

Vinyl, metallic thread, beads

3.5 x 7.5 feet

EGSo much of your past work has embraced loss and grief. Do you consider your practice therapeutic?

MT My work has been quietly giving voice to what is hard to talk about. Everyone experiences loss and grief. Normalizing emotions feels like a form of resistance that can address the distance we tend to put between ourselves and our emotions. For me, making is a means of processing. My work definitely gives me the opportunity to acknowledge, move through, and transform emotions—consciously or not. I recently got a hand-written letter from a woman whose relative had passed away during the height of COVID, and she couldn’t physically say good bye to him. When she encountered my work For Love Alone (2016) last year, she said that sitting with it for a long time gave her the closure she needed, after which she wrote the letter.1 It seems like it could be can be a lot of weight to receive emotions like this but at the same time I’m not scared of grief and I can listen and be a safe space for them.

EGCan you share more about For Love Alone?

MT For Love Alone is a star quilt made out of vinyl that is sewn into the shape of a body bag. It was inspired by the experience of watching the coroners come in carrying a simple, solid colored bag the night my dad passed away. After this I was compelled to create a body bag as an act of saying goodbye and as a way to honor my dad. Although the body is only carried in this bag for a small moment in time, I couldn’t bear the thought of him being in something so plain and simple. The colors of the star are based off of a quilt my mom made for my dad when they were first married. She made it as an act of love. The beads in For Love Alone add a decorative quality to the piece and the arms of the star wrap around the bag as a way of wrapping and holding a body in that love.

EGOne way I connect to For Love Alone is as an act of reclamation known as imagery rescripting: the ability to change the content of a distressing or traumatic memory by recreating aspects of it. I wonder how processing emotions became so integral to your making?

MT I often say I wish my work would be about other things. So much of it has come from things that are difficult. Each time I feel I am about to make work that is not about difficult things, there are more difficult things to feel.

My mother did hospice care, so I have been around a lot of death and dying that way. It wasn’t until college that I personally experienced death, when I lost my first close friend. Then I lost my dad, my best friend, and then my grandpa. The following year, I lost more close friends. These experiences can instigate a loss of control of oneself. We all process differently. I’ve learned I always have to keep going somehow. I don’t know. Death has felt continuous, affecting my relationships—as in, how do I create relationships without the fear of losing someone? This solo wasn’t going to be about another kind of loss. I had started other things, but they made no sense when I was in the midst of grieving once again. I can’t force work. I almost needed to postpone the show until I remembered I know how to make from this place, and I have to.

EGIt’s so much loss. Thank you for opening a space through your grieving for others to connect to. At the same time, I too wish that one day you can make from a non-grieving experience. I’ve been thinking that relationality is intrinsic to the emotional generosity in your work. Not only do you connect to and through yourself to all that is being mourned, but you do this through your sensibility with textiles, in a practice that feels both honorific and expansive. You’ve often said you enjoy the practice of pushing boundaries of what textiles are considered to be. Many existing reflections on your work have exemplified your ways of supplanting the expected with the unexpected. For example, you’ve used materials such as bottle caps, photographs, reclaimed plastic or panty hose to mimic or reference natural fibers. What I also notice through your work is the inherent purpose of textiles over time as a tool and form of relationality, of communication. Textiles have histories as coded and storied patterns—literally, languages legible within specific communities, or as gestural languages of love and duty imbued in making, giving, and receiving. I’m trying to say it’s both the emotional and material intricacies, the labor and the time archived within, that make your work feel relationally devoted.

MTI hadn’t thought about my practice like that, but it’s true, and I’d like to think more about this. Maybe we can come back to it.

I wanted to return to something you asked, about how my emotions and my work became tied. If I think about it again, it’s actually because of my mom. Throughout my childhood and even today, my mom has always talked about normalizing emotions and valuing intuition. All my car rides to school or anywhere else were about this, so I either consciously or subconsciously soaked it in. She also taught me that it is okay to receive peoples’ strong emotions, yet have boundaries. It has probably influenced me in ways I don’t yet know. If I think about it, it might relate to the instinct of making itself, as in I try not to force things, including my work. I have a practice in which I work intensively and then take rests. I can only create when it feels right.

fabric and plastic pellets

approx. 83.5 x 100 x .5 inches

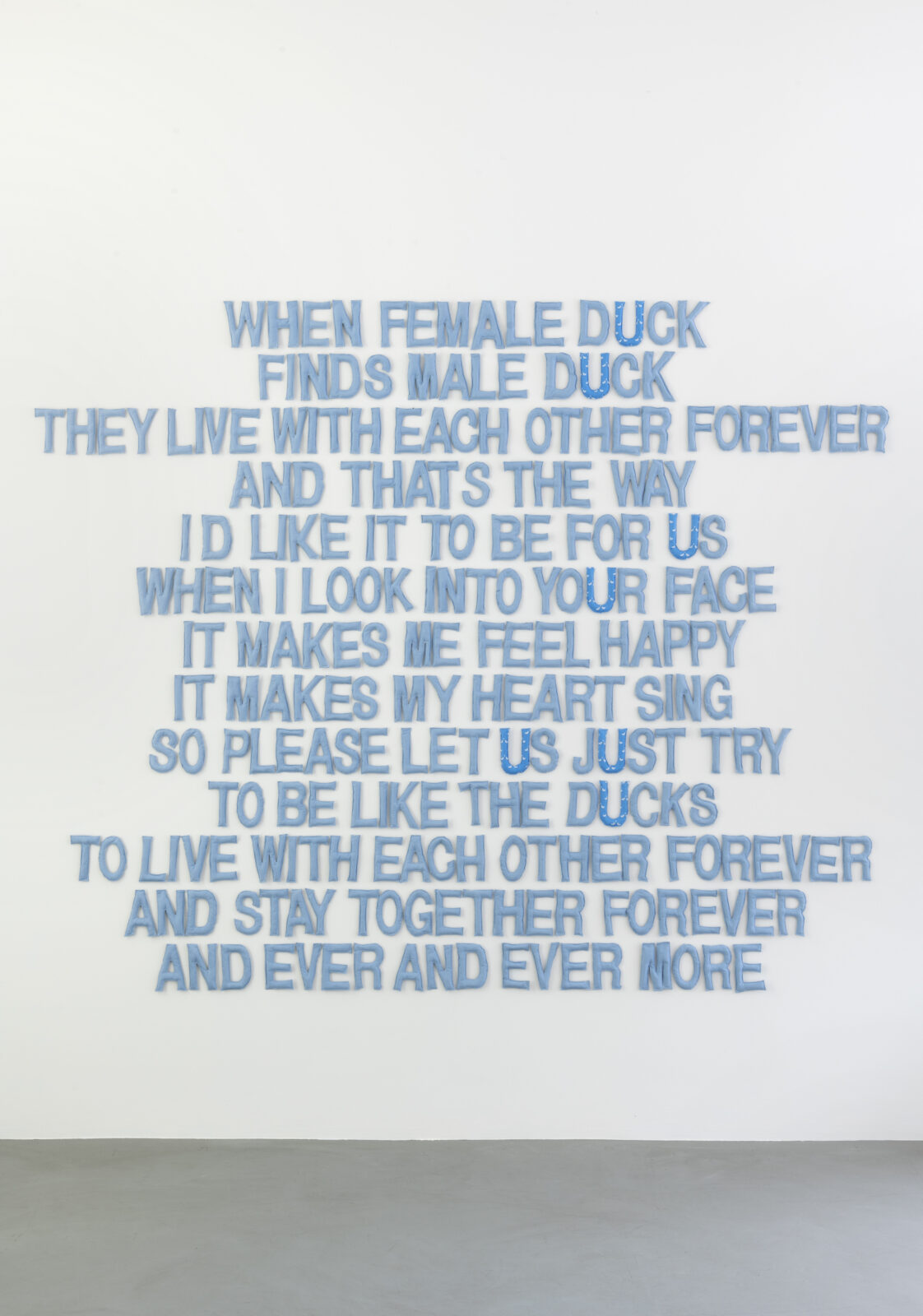

EGI’d like to tug at your mention of intuition, which is something you pronounced almost immediately during our first studio visit. As we were standing at the working station where Love (2022) was being made, one of your assistants, Nadonna Nidaanis, was carefully tracing hand-sized letter stencils onto solid blue fabric, with duck-patterned yardage folded to the side. I asked a wide-open question: “From where does your work begin?” You answered as broadly, and quickly: “I work intuitively, or I try to.” This acknowledgement and effort to intuit—to make and trust from the realm of intuition—flagged its importance as both an essential methodology and technology of knowing in your practice. As an example of intuition’s role in your works’ becoming, what about Love?

MTI’m sensitive to materials. I take a lot of time communicating with them. I do a lot of testing and sampling in the studio. I plan but I can know only some elements as I start a work, and the rest I trust I will learn along the way. I can start making a piece like this with one material in mind, and it will show me, through its physicality, if it’s the one or if it’s not in tune with what I need to convey conceptually. Love (2022) started with all the wrong materials. For me, those moments of realization are made as if I am an external viewer—though one that is inside my body—telling me it’s not right. That is one part of intuition, and I use it based on feelings in my body. It’s like language: first is a physical register of emotions, consciously or not, then there is language to communicate that. For Love, I needed fabrics that were calming—like the feeling I had with the person the work acknowledges. I walk through the fabric outlet SR Harris until colors and patterns jump out at me. This one is calming blue, it’s child-like—like the love it speaks to. The duck pattern is literal in relation to what it spells out, also reflecting the simplicity of childhood love. Nadonna Nidaanis and I and many more folks will soon be technically figuring out how to resolve this work. While I know need to make Love, it’s hard to speak about beyond its physicality.

EGLove replicates a poem you wrote as a pre-teen, in 2001. Many of your works begin by revisiting your journals, your past writings. Sometimes you give literal form to language, usually English, sometimes in Ojibwe.

MTI don’t think of myself as a writer. Sometimes I say I’m an artist because I lack words. Maybe it’s getting older and feeling more confident. I enjoy using words, in a minimal way, and seeing how the materials interact with words. I guess this goes back to connect to the question of textiles’ communicative histories, in a very literal way. Some works begin with text but don’t spell anything out. Like with The Equivocator (2021), it came from what I wrote in a journal when I was having a hard time dealing or figuring out what was actually happening in an abusive relationship: “A belly tied in knots with the red flags you so delicately placed but insisted did not exist.” It’s important to write experiences down in those situations.

rope, wire, stockings, thread, ribbon

3.5 x 5 feet

EGYou read Love aloud to me so matter-of-factly, with so much respect to your child self. I began imagining your pre-teen world that made you locate, and even long for, an ideal love modeled by perennially monogamous waterfowl coupling behaviors! It was only when we moved to the next work-in-progress that I realized the addressee of that childhood poem is central to the whole exhibition. That’s when I rethought the exhibition title and realized the immensity of your heartbreak.

MTIt’s hard to believe, but the exhibition is me processing one relationship. I’ve loved this person since I was a kid, and we just dated again and just broke up. As the works take shape, I’m continually wondering how to talk about them, and the exhibition as a whole. How to keep this person anonymous, keep privacy, and be honest with myself and do this the way I need to. I want to communicate generally, but I won’t be able to do that. I will need to speak about this relationship, yet I know that speaks to all relationships, great love, and relating to loss, too. This one is a such a deep, long love history, it is almost absurd. When it is too hard, I need to remind myself that audiences will have a relationship to their own emotions if I share mine. Heartbreak is universal. We have all known it; we can all remember it.

EGIt’s been helpful for me to process heartbreak through death’s grieving processes. There are multiple deaths—of the vessel that was the relationship, of a partner no longer physically there, of the aspects of self that we are attached to as part of being with them, of habits to project a future together, etc.

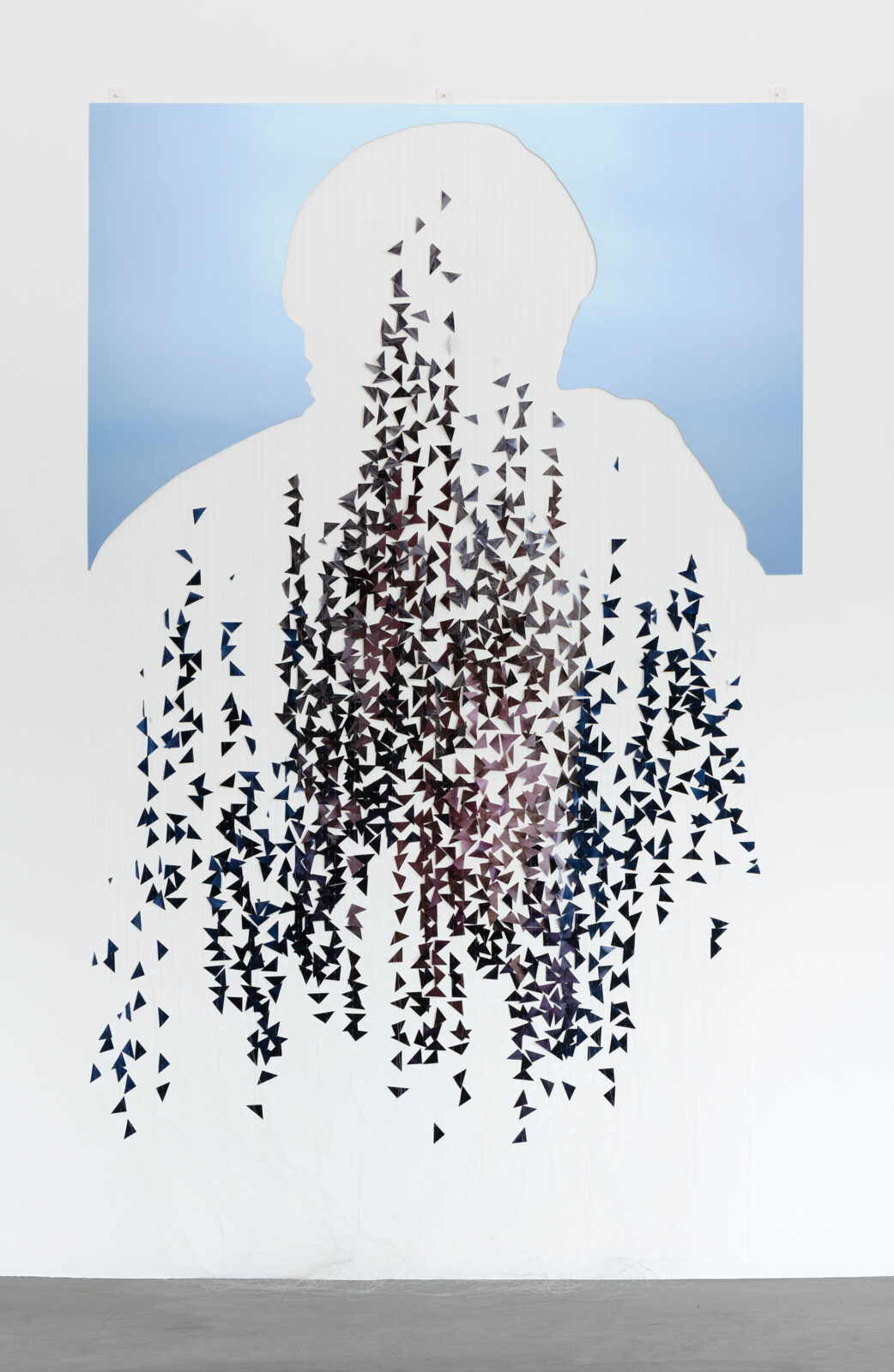

MTIn endings, how do they, and how do we, exist after their physical presence is gone? All kinds of loss—heartbreak, death, abandonment—these are traumas that affect memory and perception. Breaking up is a literal fragmentation. I’m thinking about this through photographs. I’m thinking about the silhouette a lot, the image of a person, the blank that disrupts the image. It’s so hard to look at photographs, but it’s part of it. These photographs were taken on a cloudy day as we were looking for agates. We had an agate thing. We had a special connection to northern Minnesota. This image of him—I’ll print it on paper and then cut him away, from which his image will be cut further into tiny triangles attached to clear string. Little pieces of him falling.

EGIt’s like a large-scale version of the post-breakup cut-away jab. Its analog-ness reminds me of the way you’ve treated many photo-based works, as if the photograph is a textile: cut-able, weave-able, sculpt-able. I’m especially thinking of the triangular appliqué in Fragments (2016), a quilt-like sculpture about fearing the fading and loss of memory.

ink jet print on paper and nylon filament

approx. 75 x 44.5 inches

MTYeah, I guess so—cutting and treating photographs like a textile. Working with an existing image brings its own challenges. There’s another photograph from the same day, of both of us—me holding him. If I cut that out, it would be empty arms with his image falling. It may be too complex, with only the ground for reference.

EGHeid Erdich’s poem “Ghostly Arms”2 comes to mind. It references a galaxy called M106 that has an extra pair of arms that strangely contain no stars, but maybe exist because of the violent churning of matter around the galaxy’s black hole. An excerpt:

Arms across the universe reach

and grasp at nothing

but the emptiness of space.

We never know the moment

we end it.

How warm were my arms

the last time I meant it

when I nested you in them?

How ghostly and misaligned

our caress would be

if we held each other now.

We never know

the moment we end it.

MTWow. That’s perfect. Actually, for the title I’m thinking of either Ben Howard’s lyrics “Gracious goes the ghost of you,” or the phrase “ghost of you” from Justin Bieber’s “Ghost.”

Lyrics are always part of my making. It’s obvious to say but lyrics are so powerful already, and then they get paired with sound. It’s visceral. It fascinates me how lyrics and sound meet in the body. My dad was a musician, and I heard him play at home and here and there. My mom always played what felt like fun music, mostly rock ‘n’ roll, and piano.

EGActually, I’ve been thinking of this whole exhibition as a breakup album, each work a track.

MTI like it. It makes sense.

inkjet print on paper

22.25 x 76.5 inches (overall)

EGIn your Just Friends album, my sense is that you’re not screaming or wallowing, not raging confessional. There’s some irony now and then but there seems to be no blame. There’s maybe a tinge of anger but definitely no shame. It feels very present and anthemic in its interiority, like an honoring of your grieving.

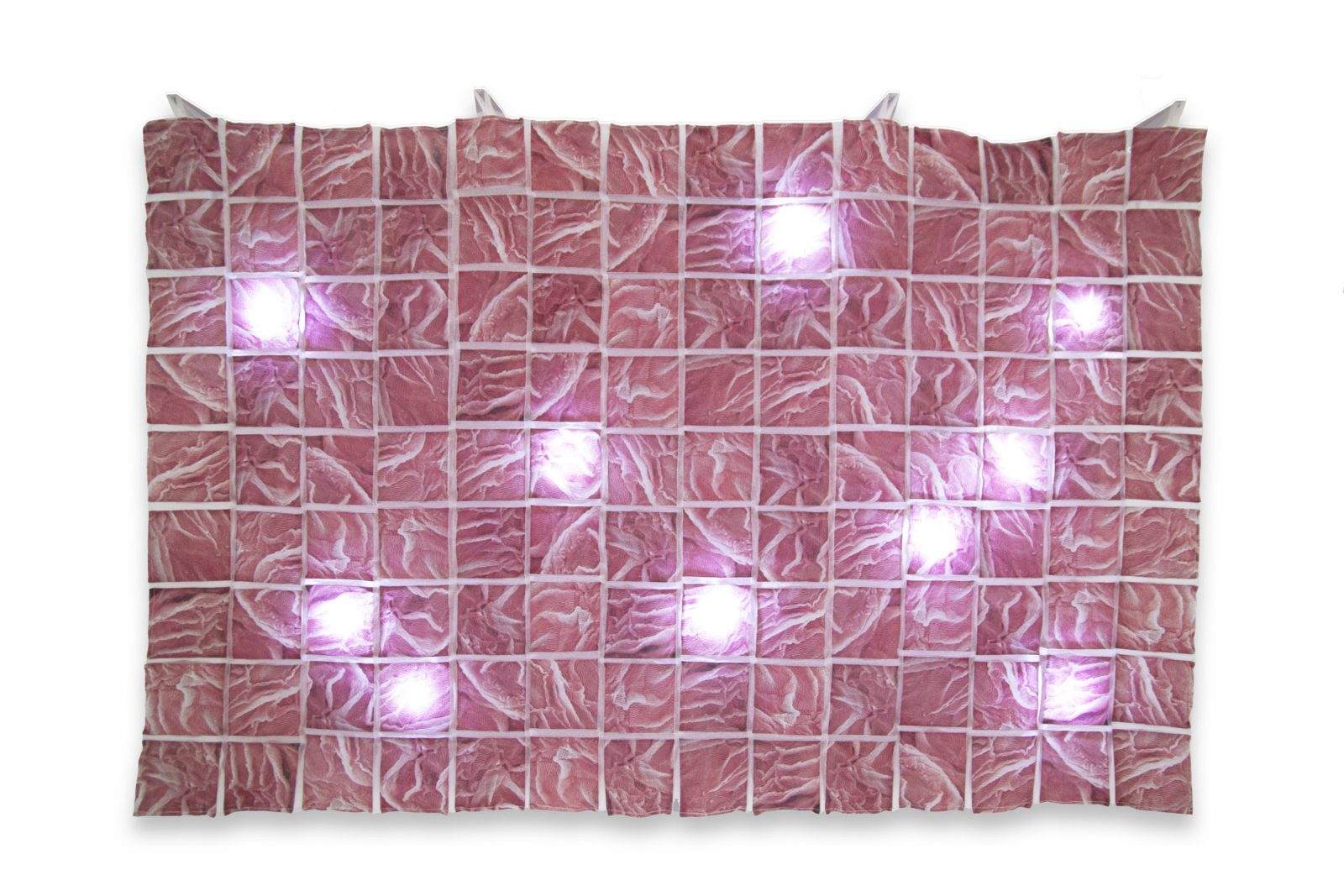

MTIt is an honoring of heart, knowing my intentions and emotions. I loved and cared for this person; I still do. Each work is a personal narrative. I feel different emotions on different days. Thinking about music—highs and lows, crescendo and decrescendo. There is grief—the inability to spend time with that person feels like such a loss. There are memories revisited, like in Ghost of you. There’s trying to find neutrality, calm, a place to move on from. Maybe that’s like Quantum Entanglement. Thinking through anger—Intentions is probably that track. It’s another photo-based work, and another based on text, actually. I used my body to form letters. They’ll be arranged to spell “my body feels like a place you only wanted to visit but never call home.” When I made it, I was, of course, thinking about one human, but I am thinking about men in general. I feel like that work is probably the most direct and pointed that may be perceived as anger; but it is hurt—the softness of the images maybe helps communicate that. It’s quietly loud. All the works are filled with so much time and love, too. It’s also not knowing how to get closure, or not even being ready to want closure with that person, but deciding to create the closure through making this exhibition. The work Breadcrumbing is probably most connected to closure.

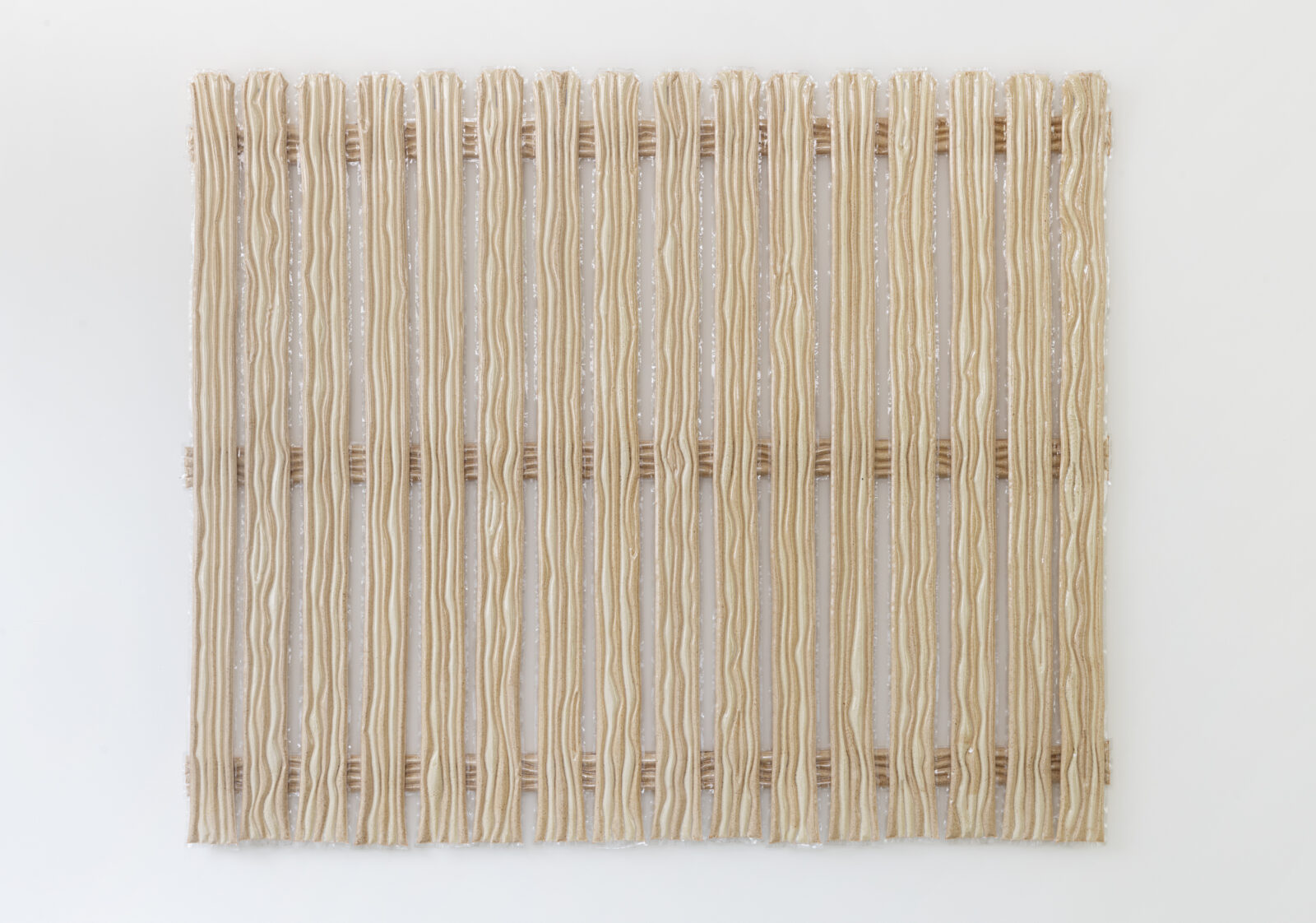

EGBreadcrumb can verb?

bread crumbs, vinyl, metallic thread

61 x 75 x 2 inches

MTYeah, I recently learned that breadcrumbing means leading someone on. In my last relationship many things were promised, many acts of service. Things that would continually not happen, or some were started but remained unfinished. It left me in a weird place, like expectant and waiting, and strangely feeling without agency, and wondering what things mean. One promise was a dog. It never happened. So I got my own after the breakup. Another promise was building a fence around my house. I just finished building my own fence. It was sad, hard, and as it went on, it was really empowering. When it was finished, I began building Breadcrumbing. I started testing different brands of breadcrumbs, their colors, consistencies. We will sift the crumbs into the “fence posts” which are clear vinyl bands sewn with metallic thread. I like metallics. They make things feel special somehow.

EGIt’s entertainingly faux; a parody of a fence. I like the paint-by-number effect of the wood (crumb) grain.

MTIt won’t pretend to function either. It will be mounted on the wall. It’s an illusion of a fence.

EGA façade in all of its physical and emotional forms. I’m glad for your real fence too—that bit of literal (en)closure.

MTWinston likes it, too.

fabric, plexi-glass, quilting, laser cutting

33 x 50 inches

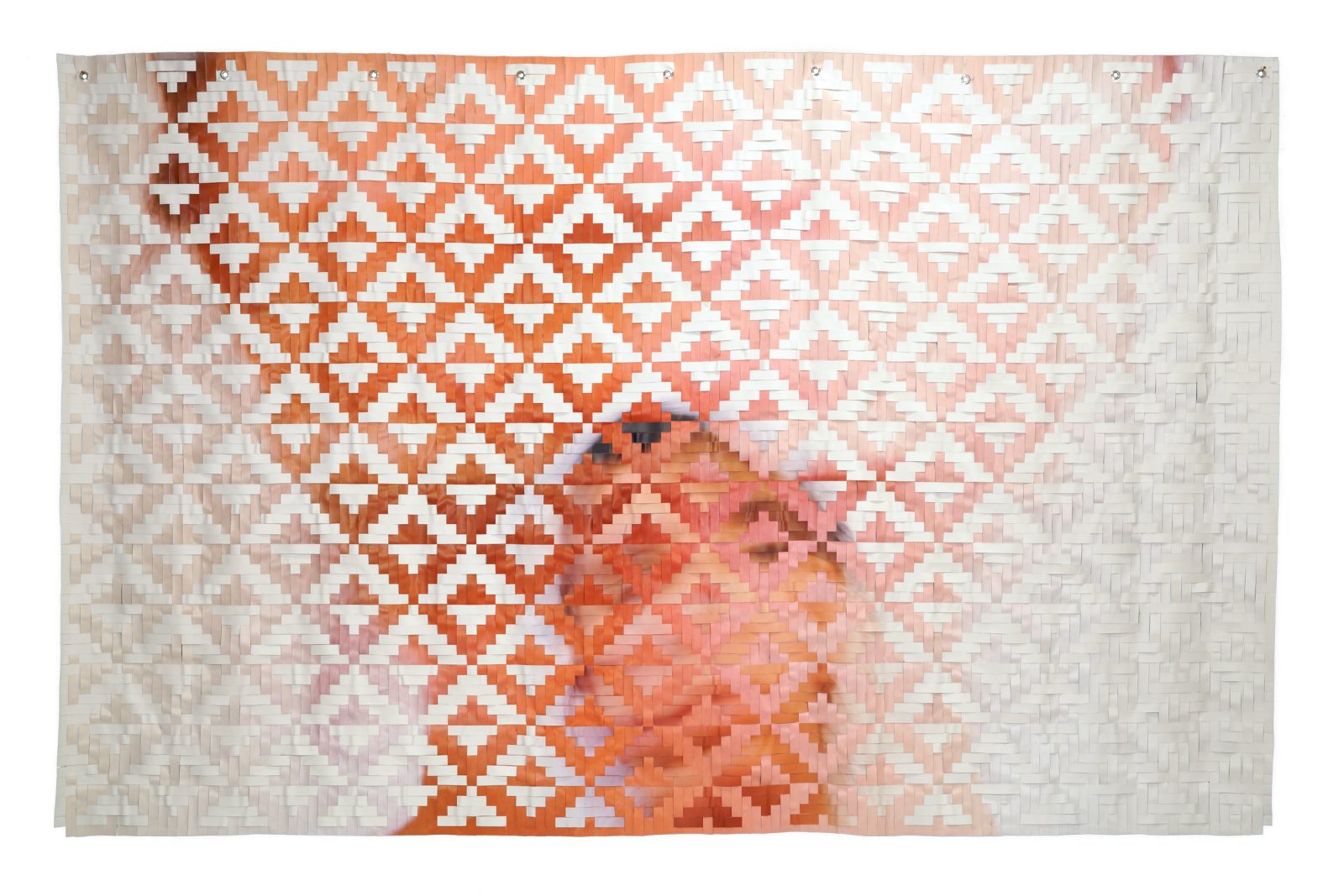

Vinyl photo-weaving

9 x 11 feet

EGBefore we end, I want to return to the body. You speak of the body as an emotional site and often visualize and render the physical body’s interiority: Quantum Entanglement’s adorned, fleshy hearts; The Equivocator’s ribboned guts; Swallow’s (2013) patterned cancer cells; charted blood (quantum) in Family Portrait (2014). Even when the body is present as a figure, it is abstracted: In Loss (2015) and Intention’s blurring of the self. And some works, like Intention, literally conflate body and language.

MTSpeaking from the body feels like I’m speaking from the self. It feels natural, personal, and honest. It sounds simple but we can connect because we all have bodies.

EGMore poetry comes to mind. Layli Long Soldier3 ends a poem, “where in the body do I begin,” and in another, words are placed in an arc: “All is experienced throu/g/h/ the / body /someone told me.”

MTI locate feelings and intuition in the body. We call intuition a sense, something without a place, but it’s through the body. In thinking about love and care, we can love through words but also presence and physical touch.

EGLove languages come to mind.

MTI’m revisiting them.

EGMe too. Quantum Entanglement made me think about the recent decades of study around the energy field made by the heart. There’s a reason the heart was chosen millennium ago as the organ associated with feeling-knowledge. It’s literally a radiant site, even more so than the brain.

photo transfer on fabric, beads, and thread

approx. 41 x 58.5 x .75 inches

MTThe stuffed fabric hearts of Quantum Entanglement will stretch across the wall connected by a ton of beads that cascade between them. The hearts are made by phototransfer and look like steaks and that’s kind of the joke.

EGRaw? Tender?

MTYeah. It’s also just a really sincere piece, about that soul connection with someone, when people pop up in your life whether you want them to or not. It can be called a spiritual connection—that unexplainable thing that you feel with someone. Even after the “end.”

Maggie Thompson, Dakobijige / She Ties Things Together, August 6–November 30, 2021, Miikanan Gallery, Watermark Center, Bemidji, Minnesota.

Heid E. Erdich, “Ghostly Arms,” National Monuments (East Lansing, MI: Michigan State University Press, 2008), 57–58.

Layli Long Soldier, “(1) Whereas Statements” and “Dilate,” Whereas (Minneapolis: Graywolf Press, 2017), 61, 35.