Homelands Lost, Constructed, Reimagined:

An Interview with Pao Houa Her

archival pigment print

32 x 40 inches

Pao Houa Her’s art is, in many ways, about the pull of home. A Hmong refugee who arrived in the United States from Laos as a child in the mid-1980s, much of her photography captures elements of her people’s stories of displacement and yearning for home, either a geographic place or a state of being anchored by safety and belonging. Her Attention (2015) series presents lush-hued military-style portraits of uniformed Hmong men who fought on the Americans’ behalf in secret guerrilla units in Vietnam but still haven’t been officially recognized for their valor in their adopted country. In the case of After the Fall of Hmong Teb Chaw (2017), it’s more a hunger for a literal homeland: the series of portraits focuses on elder Hmong women scammed by a community member who fraudulently promised a stake in a homeland for Hmong people back in Southeast Asia. Her most recent project looks at landscapes in and around Mount Shasta, California, an inhospitable terrain now home to hundreds of Hmong Americans, suggesting a teb chaw, or home country, gained.

After the Fall of Hmong Teb Chaw series

archival pigment print

52.5 x 42 inches

After the Fall of Hmong Tebchaw series

archival pigment print

52.5 x 42 inches

These works can be deceptive in their straightforward documentary approach, one that speaks the language of traditional Southeast Asian portraiture but upon closer inspection reveals a deeply conceptual underpinning. The Attention photos feature men who, ignored by the US military which conscripted them and still seeking validation, honor themselves by wearing uniforms purchased on Ebay and performing military rituals learned on YouTube. The elders of Teb Chaw, photographed at either a St. Paul senior center or the nearby Como Conservatory, appear to be sited in the lush foliage of Laotian jungles, but subtle details—a visible extension cord or security camera—puncture the illusion of a tropical paradise. In this way, Her’s art straddles worlds, that of her birth country and her adopted one, the photographic practices recognized by her community and the conceptualist leanings of her Yale pedigree.

Based in Blaine, Minnesota, Her is having a momentous 2022: she was featured in the Whitney Biennial, Quiet as It’s Kept, through multiple pieces, including a wall of rotating works on the Whitney’s fifth floor. She won third prize in the National Portrait Gallery’s Outwin Prize (on view through February 26, 2023). And, she’s the subject of a Walker Art Center solo show, Pao Houa Her: Paj quam ntuj / Flowers of the Sky, the first museum showing of the Mount Shasta series. She sat down recently with writer Paul Schmelzer to discuss her practice.

PSWhen you realized you wanted to pursue photography as your art form, was your spark an artistic impulse or a photographic one?

PHHI don’t know. The first time I realized I wanted to be a photographer was when I saw Wing Young Huie’s exhibition at the Walker [in 1998]. One of his photos of what looks to be a Southeast Asian man sitting down getting his hair cut was made into a postcard. And I instinctively knew that was a Hmong guy. I’d never seen a photograph like that before and decided that I wanted to make those types of images. It was powerful that here was this man who was photographing not only people who looked like me, but also he was literally photographing my people. My grandmother is in one of his photos. A uncle that had committed suicide years before was one of the people he photographed. I had never seen anything like that in all the photographs I’d seen of Hmong people, but also I realized there are stories in that, stories I felt like I could make.

collection Walker Art Center

PSI was struck by a quote from your 2016 conversation with Wing. “For me photography is never real. It’s fiction.” Then you clarify that “maybe it’s not that photography is fiction, but photography is selected memory.” I’ve noticed that quite a few writers and galleries have quoted that since then, or more accurately, a fragment of it—the fiction part instead of the clarification. Have you changed your thinking on that over the years?

PHYeah. Photography’s not real for many reasons for me because the photographer gets to decide what to choose, how to frame things. I think about photography as memory, like snapshots. So when we’d go on trips, my husband loved documenting everything. But when I say everything, I don’t mean everything everything. He didn’t document when he was mad at me, for example. So all we have of all of our times together are all these happy memories. If I was a stranger looking through a photo book of my entire life, I’d think that my life was really great because it was all these happy moments. But there’s so much more to that than these happy moments. And so when I say I don’t think photography is real, I think it’s more fantasy than it is real.

PSCurated Realism?

PHHYes. It’s a curated reality. It’s a truth if you want it to be a truth.

PSIn your work there seems to be a deep interest in remembering and forgetting: remembering the old ways in Laos, a hazy recollection of what a homeland could have been or could be, the forgotten service to Hmong men.

PHHI am really interested in those things. I’m also interested in the way we fantasize when we remember Laos. My understanding of Laos is through my grandmother’s telling of Laos. And her remembrance of Laos is really different from the actual Laos.

PSWere you surprised or let down when you returned?

PHHI had this fantasy of what Laos was going to look like because of my grandmother. Every time she came over, she would sleep in my bed, and I would lay next to her. She had this really soft body, and I would just lay, and I would say, “Tell me what you were you like when you were young.” She would tell me these stories about how she helped her mother in the morning. And I would ask her what it was like when she went to the garden, and she would talk about her long walks. I have these visions of really green junglescapes and lush garden fields, and it was completely different when I went to Laos. It was really brown. In the 1940s and 1950s, when she was growing up and maturing, maybe those were different times. Maybe things have completely changed.

But, also, I feel Laos is sort of a time capsule, in a way, in that the home that she lived in is still there—it’s being occupied by somebody else—and that remains the same. The only difference is they now have these long electricity lines that go into these makeshift bamboo huts; they now have electricity and internet and cell phones.

PSI love how lush and idyllic the portraits feel, of the women in particular [After the Fall of Hmong Teb Chaw, 2017] and even the “mail-order brides” [My Mother’s Flowers, 2016], but there’s always something that punctures the fantasy. If you look closely, you can spot a light or a security camera or an electrical cord, or perhaps the lighting is too harsh. It’s all very purposeful: the illusion and the puncturing of the illusion.

The Imaginative Landscape series

archival pigment print

20 x 25 inches

The Imaginative Landscape series

archival pigment print

20 x 16 inches

PHHRight. It’s very, very purposeful. I think it helps bring one back from the fantasy of thinking and looking at these beautiful people, right? Like, oh, wait, there’s something wrong with their face in relationship to their body. Or wait, this isn’t a jungle. It’s actually this made-up space. Right? So those things for me become really important in the work.

PSBut the viewer may not really get that. I didn’t at first.

PHHThat’s what I love about photography and its ability. I love that there is a language, whether the language of photography or just the language of looking, that not everybody understands, or not everybody is privy to the notion of image-making. I think everyone in the Hmong community knows that what I’m making is a really traditional Hmong portrait. But it reads really different in different communities. And I like that it reads so differently in different communities. I love the idea, too, that it’s such an easy photograph to make, that anybody can make the photograph. A Hmong artist said that to me once, and I was like, “Oh, I don’t know if I should be offended by that.” But then the more I thought about it, the more I was like, yeah, of course! We all have that photograph in our house. We all can make that photograph. We know how to make that photograph because we’re so used to making that photograph.

PSWhat audience do you have in mind when you make your photos? At your 2018 Minneapolis Institute of Art talk you said it’s largely the Hmong community, which I had assumed, since your aesthetic doesn’t seem to cater to non-Hmong, or more specifically white, audiences. It’s not an exoticizing view, nor is it purely documentary.

PHHI’ve always had a hard time thinking about my audience. Yes, ideally, I’m doing things for the Hmong community, but the reality is Hmong people don’t go to museums or galleries, and that’s mostly where the work is shown. So, while the work is for these communities, I don’t expect the communities to access it right away. This might feel really pretentious to say, but I think my work is for the Hmong community, but maybe not for this generation but for future generations. So that they can look back and have this be a record of sort. But perhaps not a factual record. I think the veterans project [Attention, 2012–2014] is really problematic because there’s something about these old Hmong men wanting to be so much a part of something. And the extent that they go to become a part of an organization that doesn’t give a shit about them. There’s something to digest and something to dissect about that need that I’m also really interested in.

PSThat’s a fantastic project because it’s so complicated. When I first saw it, I didn’t read the label, so my takeaway, having known about how Hmong fighters haven’t been recognized by the government, was: that’s great that she’s putting Hmong men in a museum; at last they get their recognition. But there are so many more layers. It’s a way of honoring these men, but there’s also a bit of a critique in it. I understand that Democrat Jim Costa introduced the Special Guerrilla Unit Veterans Service Recognition Expansion Act of 2021 last May, and there’s been no action on it yet. So there still is no official recognition for Hmong service?

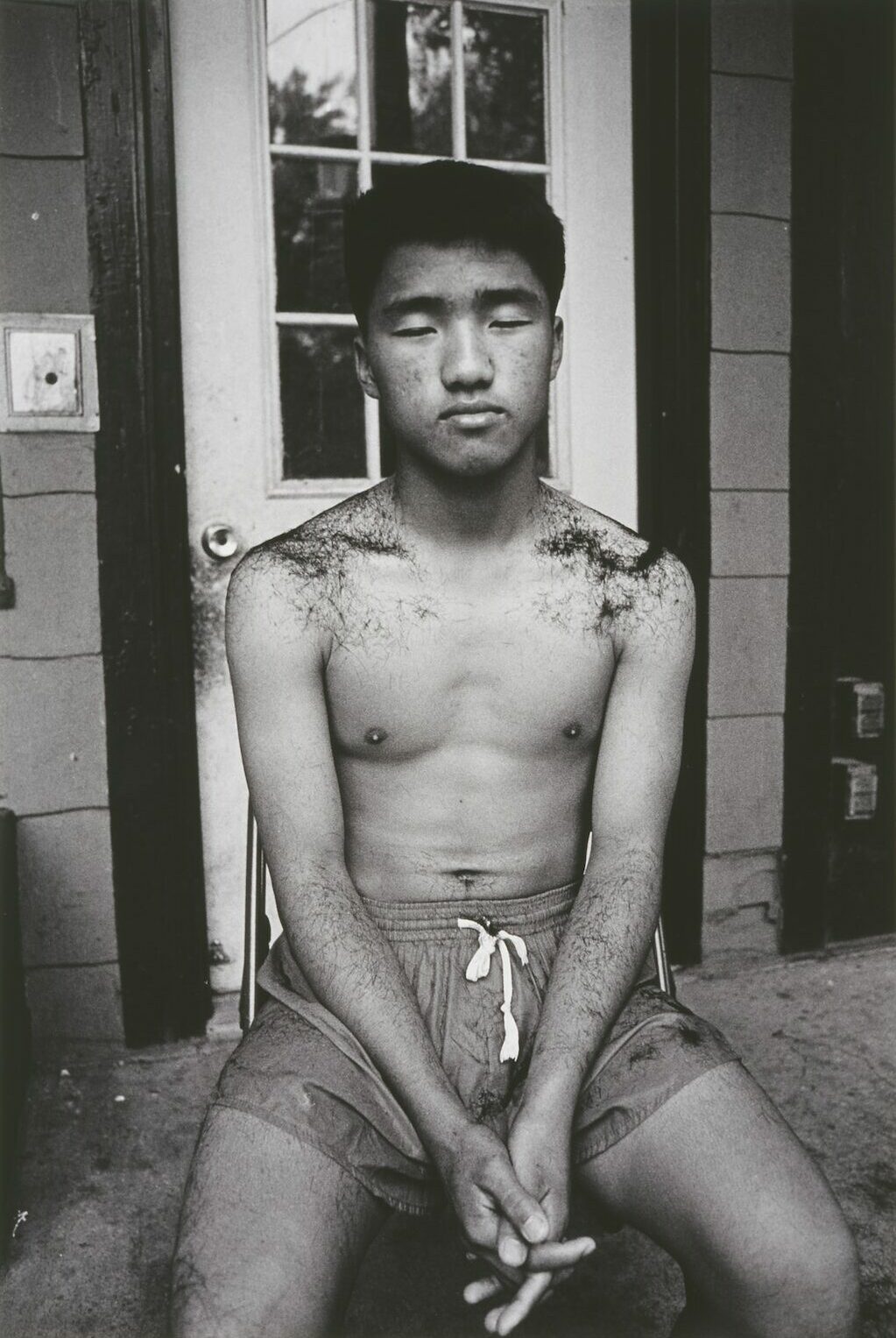

Attention series

archival pigment print

50 x 40 inches

PHHNot at a national level. There’s some recognition at the local level. It’s funny: the state of Minnesota has erected a sculpture with Hmong people in service. And, one, it looks like a penis. Then two, it’s made out of bamboo, and the US FDA deems bamboo an invasive species. So there are so many things to read from that. But the thing that’s really fascinating is there’s this notion that we can’t bring any of that up because we should just be happy that we have a statue. That’s always been the counterargument to anything that’s brought up.

PSNone of these Hmong soldiers are named. Why not? Do you run the risk of contributing to the erasure they’ve gotten from the US military?

PHHI get that question a lot, and it’s one I go back and forth on. One is because of the Stolen Valor Act. With these men, the uniforms and the medals that they wear are not US sanctioned. They’re not provided for them by the United States Army. They’re going out and buying their own uniforms, their own medals, their own pins, and they’re giving it to themselves. There’s that aspect.

Then one has to wonder: if they were in the US military, would they be getting all that? Maybe they would; I don’t know. Then the other aspect: I get that the United States Army has completely forgotten about them and that it’s important to them to be seen. And, as a person who’s making these photographs of them, maybe it’s important for me to name them. Maybe I am contributing to that continued erasure, but also I feel like: why is it up to another Hmong person—why is it up to me to do that, to give them names, when it should be the job of the people who are erasing them?

PSTell me how you learned of this story.

PHHIt was wild. I was home for a weekend from Yale, and my dad was like, “Hey, an uncle passed. We should go and pay our of respects.” I brought my camera and went with my parents. The funeral started with the casket being wheeled in, draped in an American flag. Then there were four men in white suits playing the trumpet in this sort of ear-screeching noise, followed by these men in uniforms. I was just so perplexed: “What the F? What is this?”

They’re too old to carry the casket, so afterwards they rolled the casket in, and then two men performed the flag folding. They didn’t give the flag to my aunt, but they gave it to my aunt’s oldest son. They were these rituals I’ve seen online, that I’ve seen in movies, that feel familiar but also weren’t familiar.

Afterwards, I went up and asked, “Who are you guys?” They were like, “Oh, we’re the Special Guerrilla Unit [SGU] and we fought in the military.”

I was like, “Were you guys sent by the United States Army?”

“No.”

“How did you learn how to play the trumpet?”

Attention series

archival pigment print

50 x 40 inches

Attention series

archival pigment print

50 x 40 inches

“Oh, we watched this”—and they showed me a YouTube video they used to learn to play the trumpet and how to fold the flag and do funeral rituals. Then I remember this man who showed me all this paperwork. “Here are the documents of me being tapped by General Vang Pao.” He also got picked to go and learn Morse code in Thailand.

I just said, “I’m a photographer. Can I photograph you? Can I make a picture for you guys?”

They were like, “Yeah, we would. We don’t get photos made.”

The first image I made was of them behind a velvet drape. I made them, went home, and then started doing research on military portraits. I went to the National Portrait Gallery in London and saw these British paintings. I went to the National Portrait Gallery in Washington and saw portraits of George Washington and was like, “I think I’m going to think about that style.”

I had my dad contact the president of the SGU and say, “My daughter would like to make photographs for you guys. Is that okay?” They were like, “Yeah, we would love to.” The trade was that I would make photographs for them so that they would have photographs for themselves and then I would also be able to make photographs for me. Seven, eight years later, a lot of these men have passed away, and I get a lot of requests for portraits to use for their funerals.

PS: There’s both a kind of absurdity to this story and a big element of honoring. When I saw this series in the Vietnam show at the Minneapolis Institute of Arts [Artists Respond: American Art and the Vietnam War, 1965–1975], I only read it as proud soldiers.

PHHExactly. Absolutely. I think that in every other photograph I’ve made there’s this kind of complexity to the work. Not only can we be proud about these photographs, about these men serving, but maybe we can also talk about why they have to buy their own uniforms.

PSWhy can’t they be buried in Arlington?

PHHYeah. Why can’t I name them? Why do they have to give themselves pins and names? Why do they have to do this? What is it about wanting to be a part of a history so bad that you literally have to insert yourself in a history that you are a part of? Why do you have to be afraid of getting federally charged for a crime that is ridiculous when you are actually a soldier? Why is it that an elderly Hmong man is only revered when he puts on the uniform, and when he takes off this uniform he’s a nobody? Aside from these men being proud of themselves for being in photographs next to presidential portraits or paintings in museums, I’m also interested in those sorts of conversations, too.

After the Fall of Hmong Teb Chaw series

archival pigment print

52.5 x 42 inches

PSA parallel work would be After the Fall of the Hmong Teb Chaw (2017), which features Hmong elder women and has a similar kind of complexity. You’ve said in the past that even with paj ntaub, the Hmong story cloth, women did all the intricate needlework but the men dictated what was depicted.

PHHYes. Hmong culture is very patriarchal. It continues to be even in this day and age. Hmong men are more revered than Hmong women. Hmong women are tasked with doing a lot of the labor. Even though Hmong men historically have been hunters and gatherers.

In Hmong Teb Chaw, I’m fascinated by the way in which we fantasize a country or our longing for a country that never existed. Teb Chaw means country.

PSAgain, at the most obvious level, I found this project to be quite moving: I know the wrinkles on these women’s faces mean something, marks of all they’ve witnessed, here and in Laos and Thailand. Then I read the label and I realized there was so much more to the story: they’d been swindled by someone in their own community who was fraudulently promising them a life in a Hmong homeland back in Laos. So, again, there’s a part of your work that’s about honoring, but there’s a part that’s critical, too.

PHHAbsolutely. Thinking back about the Hmong veterans, there’s an element of honoring but then there’s also element of complexity that is very much apparent and a part of the work. Another layer is the fact that the Teb Chaw photographs were taken in a senior daycare center; that’s where this Hmong man has come through and swindled some of these women.

I started hearing about Hmong Teb Chaw in 2013 through my mother who works at a Hmong senior daycare. She came home from work one day and asked my dad if he would be interested in paying for land in Laos.

My dad was like, “What’s going on?” I was like, “What? What land in Laos?” In Laos, if you’re not a Laos national, you can’t buy land. You have to be a Laos citizen to buy land. There are a lot of Hmong Americans who have land in Laos, but they will buy land through a relative. “Who’s going to buy land for you?”

“Oh, there’s this guy who says he’s working with the United Nation,” she said. “They’re going to acquire Northern Laos. He has this opportunity where if you can pay $5,000, and when the Hmong country gets recognized by the United Nations, people are going to be able to move back.

The Imaginative Landscape series

archival pigment print

52.5 x 42 inches

The Imaginative Landscape series

archival pigment print

52.5 x 42 inches

I was really skeptical: “He’s working with the United Nation. Like, what?” My mom told me his name, Seng Xiong. I went online, did a bunch of googling. Then a year later I started hearing rumors about how the FBI was coming into the Hmong community and having these town hall meetings because they thought that this guy was swindling money. Then that rumble became this full-on investigation, and later on we find out that this guy was arrested in LA coming back from Laos and was going to get extradited to the United States. He hadn’t been using money that people paid him for this nation, but actually he was using the money to go to Laos and to pay for prostitutes: self-serving. His whole defense was that the United States didn’t want him, or Hmong people, to have a country and that’s why he was arrested. A lot of people believed him. They started making YouTube videos about Seng, and he had a partner who started this other YouTube channel about how Seng is being persecuted. There’s this whole backing of Hmong people.

I was fascinated by the notion of a Hmong country, thinking about what a Hmong country could possibly look like, based on stories that, again, have been told to me by my grandmother. If I could make this Hmong country, how would I want it to be?

I wanted to make this really lush greenery space. Then I thought about the Como Conservatory and how in the late ’80s my mom and dad would take us there every weekend because it was the only place in the state of Minnesota that felt remotely close to home, based on these plants and the humidity in this space. My parents could identify plants from Southeast Asia. I distinctly remember the papaya tree, the banana tree, and how fascinated my mom was that this banana tree could grow in this encased glass house.

I started really thinking again about my role as a photographer and how I could create complexity within the work to mirror these two spaces.

PSThe portraits, then, are not documentation of swindled women, it’s more an embodiment of an unrealizable dream of a homeland?

PHHYeah, and made in the style of traditional Hmong portraiture.

PSDo you have anger at someone within your own community taking advantage of people? Do you want to expose that?

My Mother’s Flowers series

found photograph, manipulated, archival pigment print

20 x 16 inches

My Mother’s Flowers series

photograph, manipulated, archival pigment print

20 x 16 inches

PHHI do. For Hmong people, the way in which we think about art and the art that we make is very celebratory. We also romanticize a lot about life before coming to America. That’s the dominant art that’s in the Hmong community. I’m really interested in the opposite of that—in the ways in which we hide things. The way in which we talk about things. The way in which we’ve been swindled. Those are the things for me that are most important and are most interesting.

I also realize that sometimes Hmong men have a hard time digesting the work I do. They have a harder time wanting to confront it.

PSDo they feel like it’s an affront or it’s too critical or too direct?

PHHLike, “Why are you spilling our beans? We are a community whose problem should stay within the community.”

PSYou also mix the real and the artificial in your work, the real foliage of the Como Conservatory and artificial flowers. Can you talk about that?

PHHArtificial flowers are huge in Southeast Asia. There are floral shops there dedicated to artificial flowers. Being an American, that’s really strange for me, but it’s not strange at all for Southeast Asian folks.

I like the plasticity of the fake flower. I love how it is always so perfect and it will never wilt. That you will never find an ugly plastic flower or a wilting plastic flower, that it’s always in perfect bloom. Metaphorically, symbolically, I really enjoy that idea.

PSYou’ve also spoken about how in your house, the American dream meant having fresh flowers.

My Mother’s Flowers series

found photograph, manipulated, archival pigment print

40 x 32 inches

My Mother’s Flowers series

found photograph, manipulated, archival pigment print

20 x 16 inches

PHHYeah. My mom loves Martha Stewart. I think she thinks about Martha Stewart as the epitome of what every Hmong woman, or what every woman, should aspire to be. She knows how to cook. She knows how to keep a house. She’s really crafty. Her gardens are impeccable. My mom doesn’t know that she has 30 people helping her. There’s this illusion. I think for my mom, having an orderly home with a beautiful bouquet of flowers, that embodies the American dream for her. She’s always tried to have a house with florals, but florals are expensive, so she found a way to navigate that by having fake flowers.

PSThen there’s the presence of artificial flowers in your series on Hmong dating profiles [My Mother’s Flowers, 2016].

PHHRight, it’s a website that connects Hmong Americans with Hmong Laotian folks. What made it so easy to navigate was that if you knew how to type in the URL, you can go on there and right away look at images of Hmong girls or Hmong men. If you put your mouse over their pictures, then their phone number came up and you could call them right away. It was for a long time the primary source for these connections to be made.

PSWhat intrigued you about that industry and the imagery that you were choosing?

PHHFirst of all, I was really fascinated by that technology. Then two, the idea of catfishing. What happens is that these Hmong Laotian women, girls, would take their picture and go to a computer shop. Then the computer guy would photoshop their faces onto another body. Then they could upload this digital file and from there would be able to catfish these Hmong American men. I was really fascinated by that, and photographically I was really interested in images that were altered. I started going through the websites and screen-grabbing all the photographs that looked heavily photoshopped, whether it be elongating the nose ridge, whitening faces to look more European, photoshopping breasts, putting faces on bodies that are sexualized.

archival pigment print

40 x 32 inches

There’s something about that—and then Hmong men saying they would much prefer a Laotian woman because those Hmong Laotian girls have not yet been tainted by Western ideology.There’s something really funny about that—and also perplexing and mind-boggling—because the visual things they were attracted to were also really Western.

PSHow do the flowers fit in?

PHHHistorically there always has been this relationship of the flower to the female body—thinking about the fruitfulness of the female body.

PSYou photographed your mom’s flowers and then you created diptychs with appropriated images from the dating site?

PHHYes. I photographed my mom’s flowers, and then there were these appropriated images, and from them I also created other images to use as studies to make other images. That was the first body of work that I made that felt more conceptualized, that didn’t feel like documentation.

PSWhat will you be showing for the Walker exhibition?

Mt. Shasta series

light box

60 x 75 inches (image size)

PHHI’m going to be showing work that I made in 2020 during the pandemic when I wasn’t able to make photographs of people. At that time I started going to Northern California, to this place called Mount Shasta. There’s a subdivision in a town called Montega, a subdivision of maybe 200 acres that have been bought out by mostly Hmong folks from either California, here in Midwest, or out east. They’re these marijuana growers. That area has been a marijuana haven since the 1960s and 1970s. But it wasn’t until recently that the local government has really taken an interest in this land because Southeast Asian folks are coming and having these illegal marijuana farms. I’m really interested in that land. The landscape of that land. The history of Hmong people in the context of agriculture.

In the 1900s, Hmong people were cast out of China and made to go into Northern Laos. Living on sides of mountains they learned to grow whatever, whether it was opium or rice, on these sides of mountains.

PSIt feels like a similar theme to earlier projects: a kind of homeland.

PHHYeah. I think the idea of desire is thematically present in all my work. I’m also interested in ideas of land and what a Hmong land might possibly look like. In California, that place looks nothing like Laos. It’s super deserty. The land was deemed uninhabitable by the United States government in the 1960s, and they were literally giving it away for free. There isn’t water there. You can’t farm there. So, again, I’m interested in the resilience of Hmong people and our collective imagination in history. Hmong people have been able to turn it into this really prosperous space.

photo by Eric Mueller, courtesy Walker Art Center

PSJust like how the hills in Northern Laos was not land that was very prized.

PHHExactly. In modern history for the first time, we have millionaires, but also at a cost, too, because while they’re millionaires, they can’t spend any of this money because it’s illegal money. There’s something about that.